|

|

|

Retyped by Cathy Knights Reprint Edition Published Online 2004 by Joyce M. Tice

|

By Fred C. Allen, Private Secretary to the Board of Managers

This Handbook includes excerpts from board of manager’s reports and an abstract of laws relating to the reformatory.

The Summary Press

1916

Online Reprint

by Tri-Counties Genealogy & History by Joyce M. Tice 2004

The New York State Reformatory at Elmira

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 |

By F. C. Allen

This building is located near the north side of the original prison enclosure and is a substantial brick structure with steel roof and brick floors. It is divided into three rooms, the boiler room being located in the centre, and the dynamo room and the cold storage room, at either end. The brick smokestack is 126 feet in height.

The boiler room is ample in size, being 60 feet wide by 86 feet in depth; it is furnished with eight, 150 horse power boilers, of approved construction. In one corner of the boiler room is located a brick-walled pit in which are installed two Worthington, boiler feed pumps with 12-inch steam cylinders, 7-inch water cylinders and 10-inch piston stroke; also two sewer pumps, an elevator pump, a feed water heater and return tank, and sundry other apparatus.

The dynamo room, situated at the right of the boiler room, occupies the entire end of the building and is 30 feet wide, and 45 feet deep. This room contains three, high-speed engines, of respectively, 50, 100, and 150 horse power, directly connected with three, 320, 360, and 800-ampere electric generators. The engines are equipped with Wright, automatic speed governors, and automatic relief valves to free the cylinders from water forced in with steam from the boilers. There is also installed an improved electrical switch-board provided with automatic circuit-breakers.

The left end of the building is fitted as a storeroom for coal; it is 30 feet wide by 86 feet in depth and is capable of holding about 1,000 tons of coal; its floor is placed several feet below the surface of the ground, to admit of increased storage capacity.

THE INSTITUTIONAL FARM.

The farm lies adjacent to the rear of the reformatory grounds and comprises, approximately, 280 acres, of which, fifty are used for pasture, twenty-five are woodlands, and eight are occupied by an apple orchard.

The land is clay loam, somewhat stony, with heavy clay subsoil, and while it is not especially fertile, the nature of the soil favors the production of pasturage and hay, oats and rye, more than the other usual farm crops. However, all varieties of vegetables being extremely desirable for the prisoners’ use, a considerable portion of the arable land is devoted to the raising of potatoes, sweet corn, cabbage, tomatoes, beans, turnips, carrots, etc. Fair results are obtained in the production of these crops with the aid of barnyard and commercial fertilizers.

In an average year the farm would yield for the use of the inmates, 1,000 bushels of potatoes, 1,000 dozens ears of sweet corn, and large quantities of the other vegetables named.

Ten teams are maintained upon the farm. When not employed at the farm work, proper, they are engaged in drawing coal and other supplies from the railway station or from the city markets, or in incidental team work about the institution, of which there is always an abundance, occasioned by construction and repair work, delivering ice from the ice houses to the several departments, carting away ashes, etc.

The woodlands support a growth of oak and pine, a considerable quantity of which is from time to time manufactured into lumber, as required for building or repair work, or for use in the trade classes.

At the rear of the farm, a small brook, passing through a ravine, has been transformed into a reservoir, covering some ten acres of the bottom of the valley. From this reservoir, water supply for the steam-plant, and for institutional bathing, and general cleaning is piped; the elevation of the reservoir above the plateau upon which the reformatory stands, being sufficient to render this practicable. In winter, also, the ice houses are replenished from this reservoir.

Water for drinking purposes is obtained, by purchase, from the mains of the city of Elmira.

A new, horse-cow and hay-bar has recently been completed, the construction of which has been accomplished entirely by inmate labor; this building includes a central, one-story-with basement structure, flanked by a one-story wing extending at right angles on either side, without basement. In the north wing are stabled the cattle, in the south wing, the horses. The central portion is devoted to the storage of grain-feed, agricultural root-products, etc., in the basement, and hay, straw, and mill-feed in the superstructure.

Two large silos, located in the angle of the cow-barn with the central structure, and conveniently connected with the feed room located in the later; and a commodious milk-house adjacent to and connected to the cow barn at the rearward side of the latter, complete the barn equipment.

The walls of the central structure are of concrete with an exterior coat of stucco. The walls of the cattle and horse sections are of wooden construction with exterior coat of stucco on metal lath. All the roofs are of slate.

Entrance to the basement of the central structure, is by double doors located at the front; and on the north side, in the rear of the barn, is located a second door. The second story has double doors located at the rear, but none at the front. The location of the barn, at the base of the hill at the rear of the institution, permits the rear doors of the second story to open at grade, while the basement doors open at grade at the front. A mechanical hay-fork having a metal track extending the entire length of the second story, is used to transfer hay from wagon to mow. It is estimated that the hay capacity of the barn is 200 tons.

The silos have sufficient capacity for storage of corn-silage for the use of forty cows.

The milk-house section includes in its equipment a large concrete water-tank, in which to cool the cans of milk as soon as the milking shall be finished, and from this tank the milk is distributed to the institution as desired. Scales for weighing, and record-blanks, are conveniently placed so that total and individual milk-products may be ascertained and tabulated for the information of the management.

In the cow-barn section, modern swing-stanchions are installed upon a suitably trenched concrete floor. The cows are stanchioned in two rows, one row facing each of the side-walls of the barn. Concrete feed troughs extend in front of the stanchions, and hay, silage and grain rations are placed before the cows by means of feed-carriers depending from overhead tracks; water is supplied from inlet-pipes, to the concrete troughs in front of the cows, when the troughs are not in use for feeding purposes.

The barn receives its water supply from the institutional mains. It has a local sewer, connecting with the main institutional sewer, and receives electric current, for lighting, by a conduit cable from the institutional power house. A small but efficient heating plant, located in the basement, furnishes hot water for the cleansings of milk containers, etc.

Each day the barn hose is used unsparingly on concrete floors and troughs, metal stanchions and stucco walls; and even the glass of the windows is daily sluiced with water and thoroughly washed. Every effort is made to maintain in all departments of the barn a high standard of neatness and cleanliness.

The institution at the present writing maintains a herd of twenty-eight tuberculin-tested cows and as before stated, it is the desire of the management to increase the number of cows as conditions permit.

The horse barn section is suitably equipped with single, double, and box stalls, and is ample for the accommodation of the teams belonging to the institution.

The various barns and other necessary farm buildings are conveniently located outside the institutional wall, where they may be easily reached from the institution.

THE GREENHOUSE.

This building, is of modern construction, located outside the prison enclosure, near the south gate. Its temperature is regulated by steam heat, furnished by a small boiler and furnace installed in the building.

In the greenhouse are propagated tomato, cauliflower, and celery plants for the garden. Flowering and foliage plants are also furnished for the flower plots, the flower urns, placed at various points throughout the corridors and grounds, and for the decoration of the several school rooms. Cut flowers are likewise supplied for the institutional hospital, the superintendent’s residence, and the chapel.

The greenhouse is in charge of the gardener, a citizen officer, who, with his group of inmate assistants, cares also for the garden, the numerous lawn shrubs, etc.

RECREATION PARK.

This park is located immediately to the rear of the reformatory, outside the west enclosure wall. A woven wire fence, twelve feet in height, supported on posts of iron tubing, encloses on three sides a rectangular space comprising about four acres, whose eastern boundary is the west enclosure wall of the institution. A closed sewer, extending along the western boundary of the park, and connected with numerous closed cross-ditches, affords ample drainage facilities. Sifted clay, compactly rolled, and surmounted by a layer of find sand, for the baseball diamond, and by a layer of sifted coal-ashes for the rest of the park, forms an excellent surface for the players to exercise upon.

Along the eastern side of the park, benches are provided for the use of the inmate population, all of whom are admitted to the games. The western boundary of the park is at the foot of a beautiful, wooded hillside, shaded from the afternoon sun; and on this slope, commanding an excellent view of the ball ground, although located outside the boundary fence, commodious seats are provided for the use of institutional visitors who may wish to witness the games.

During the month of August, a baseball league, composed of teams of the inmates, play games, scheduled on Mondays, Tuesday, Thursdays, and Fridays, with an occasional game on Saturdays, also. These games occupy the school of letters period in the afternoon; the school being discontinued during August.

At this point in the handbook, the author considers that his purpose of describing the reformatory and its methods will be advantageously served by writing the following story, of the imaginary experiences of a New York city lad, sentenced to the Elmira institution, by the court, in the usual manner.

the

institutional experiences

of peter luckey

f.c. allen

He came, with eight others, on the afternoon train from New York. Shabbily dressed, not very clean, his appearance advertised him for what he was, an "East Sider." His sullen eyes noted little of his surroundings; his listless air evidenced slight concern for his present condition, or hope for the future. Not much had there been in his life of sixteen years to incite to honest living or elevated ideals of conduct. He had small knowledge of books, and little desire or ability for sustained effort of any description. Orphaned, nearly five years since, his reception in his aunt’s family was not over cordial; hence, left in large measure to shift for himself, he easily drifted into bad company. In a moment of temptation, he took that which was not his, and as a consequence of his wrong doing was now on his way to the reformatory.

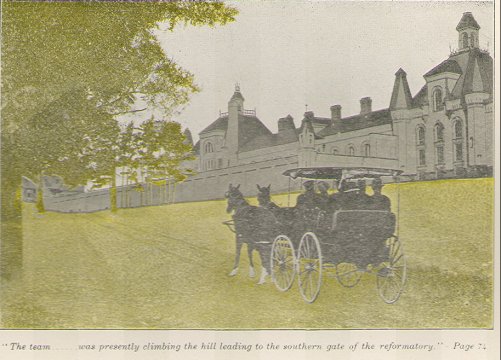

Upon the coat of the athletic young man who had charge of the group, appeared the badge of a transfer officer of the New York State Reformatory at Elmira. Standing upon the platform of the station with his prisoners, he was first to note the approach of a team of blacks, attached to a light, three-seated spring wagon, and driven by a blue coated official.

"All right boys, there’s our hack; tumble in!" said the transfer officer.

The team steadily jogged homeward and was presently climbing the hill leading to the sourthern gate of the reformatory. The stern appearing prison structure with its massive, turreted, enclosure walls, by its very nearness, forced the boy’s attention and he glanced up at it.

Although habited to environments the reverse of favorable to honest and virtuous living, he had still to fulfill his first sentence as a convicted criminal, and he instinctively recoiled as he looked at the institution, high and gloomy in the fading light of the short, November afternoon.

"The team…….was presently climbing the hill leading to the southern gate of the reformatory."

The van arrived at the gateway. The transfer officer exchanged cheerful greetings with the wall guard, as the latter operated the mechanism of the gate. The boy, listening, envied these two, over whom hovered not the dark cloud which seemed to him to be approaching more closely with each revolution of the cogged, gate wheel. One, two hours would elapse; then these men would be stepping briskly homeward through the lighted streets, free and happy, while he—but the great valves of the gate opened, the driver chirruped to his team and the van moved leisurely into the prison enclosure.

The boy‘s senses were now alert and he glanced quickly and anxiously at his surroundings. Iron gates, brick walls, everywhere. He gate through which the team had just passed, creaked as it was being closed; he looked back apprehensively and was not reassured as he saw it steadily decreasing his perspective of the outside world and freedom. Then it was closed, and he felt indeed in evil case. Again he noted the inexorable brick walls. Five years in this enclosure of brick and stone and iron! To a lad of sixteen, five years seem an interminable period of time. Would he ever live through them?

Another sinister looking gate, a combination of iron rods and bars, opened and closed upon them, and, as the van moved under the great, gloomy central arch forming the entrance to that portion of the enclosure known as the parade ground, the lad felt that he could scarcely hope ever to step forth to freedom again.

An open door, and beside it, a pleasant faced, blue uniformed officer, who glanced comprehendingly at the party, indicated that the travelers were expected.

"Only nine?—pretty slim for Saturday and coming on cold weather, too," he remarked casually to the transfer officer.

"All there was," briefly responded that official. "Lads, this is where you lodge tonight. Climb out!"

"There, there, Luckey, don’t look so blue!" he continued, encouragingly patting the lad on the shoulder as the group of prisoners, one by one, jumped from the wagon. "Elmira isn’t so bad if you look sharp and mind the regulations. Come along, boys!"

Presently they were in a large room, with wire-screened apartments where men were busy, working at account books and sorting clothing. The electrics were already alight. Peter Luckey stood, awkwardly looking about him. The transfer officer, after conversing in a low tone for a few moments with the store room clerk (the officer who had met them at the outer door,) took his departure.

The clerk turned briskly to Luckey, who chanced to be standing nearest him.

"Here, boy, quick!" he commanded: "Off with your clothes and place them in a pile over by the screen there."

The boy hastened to comply. After a hurried examination by the clerk, the raiment of Peter Luckey was consigned to a pile of garments which eventually found a Gehenna in one of the furnaces at the institutional power house. The clerk searched the lad’s pockets, and a few pennies and a button photo, found therein, were placed in an envelope, inscribed with the owner’s name and the consecutive number given him by the storeroom clerk.

"We’ll keep these for you, lad. What is your name?" inquired the clerk.

"Peter Luckey," was the reply.

"All right, Luckey, when you go home these things will be returned to you. Now stand one side and make room for the next man. You—there—with the curly hair—come over here!"

A short time sufficed to subject the rest of the prisoners to a like process; then, after having their hair trimmed, all were conducted to the bath room. Ten minutes beneath the warm spray, with a vigorous application of soap and towel, and they were returned to the storeroom, and a complete new suit, including underwear, cap and shoes, furnished each of them together with a number of other useful articles. Luckey was quite impressed with the magnitude of his possessions, which included a blanket, sheets, towels, a wash-basin, various brushes, broom, dust-pan—a whole armful of property. He put on his clothes and stood watching with interest the deft motions of the barber, a prisoner, he concluded, by his dress, which was identical with his own. Glancing about he noted that all the assistants were similarly attired. If he could only have some such pleasant employment as have these boys, he thought, imprisonment might not be soo bad as he imagined.

But he was particularly interested in the boy he had first noticed, who had been busily plying his vocation upon several of the new arrivals whose beards required this attention, and had just finished the last one. How foolish, thought Peter, that a young fellow so skillful, should allow himself to commit crime sufficient to incur imprisonment.

"Dat’s a smart barber!" he ventured to say to the store room clerk.

"Learned all he knows about it here;" was the terse response as the officer turned away to "line up" the prisoners for the march to their rooms.

Peter’s mind was so occupied with the thought of the quick, graceful motions of the barber; the apparent ease with which he accomplished his work; and of the pleasant, contented faces of all the prisoner assistants, that he but carelessly noted the passage of the party through long, high, wide corridors, with lofty, barred windows and hundreds of cells rising tier upon tier to the vaulted ceiling.

He was startled when the officer suddenly plucked him by the shoulder and steered him up the iron stairway leading to the second tier of cells. Midway of a gallery extending along this row of rooms the squad was halted.

"Man at the head of the squad, drop out!—The one at the left—that’s the one! Look on the inside of your cap and you’ll find your consecutive number. Drop out and go into this room."

"T’ank yer, sir," said Peter, mechanically. He stepped gingerly upon the one stone step, and passed through the narrow doorway. Clang! Went the door, closing behind him. Creak—the key turned in the lock.

Onward moved the squad, and he was left alone.

While not absolutely his first experience of being locked in a cell, as he had passed several days in the New York city prison after he was arrested, nevertheless, the closing of the cell door carried with it an impression of finality, most depressing to Peter Luckey.

He gloomily seated himself on his small, iron bedstead and meditated about many things. How he wished for the power to render himself invisible, that he might so place himself outside these walls. On the other hand, he reluctantly admitted certain improved physical conditions. He was clean, decently clothed, warm—better off, in many ways than he had been for a good while. Still---

He heard the steps of the officer, returning after locking the other prisoners in their respective cells.

"Why do you sit, moping in the dark? Light your light!" he called briskly in at the door.

"I didn’t know as I had none. Oh, yes, sir, I see it now." Peter turned the button of a small electric bulb which projected from the wall above the head of the bed, to the left of the door, instantly flooding the room with light.

"Now, jump up, quick and make your bed and place your things in the cupboard, there. When the nine o’clock bugle blows, you must turn out your light and get into bed. If your light is burning after nine, you will hear from it," tersely concluded the officer. "Good night, boy."

"Good night, sir." The officer moved away. Peter Luckey commenced, awkwardly enough, to arrange his possessions. At the side of his room, opposite the door, was a wooden cupboard, on the shelves of which he placed several of the articles. Clumsily he spread his sheets and blanket on the mattress lying on the bedstead, placing the pillow-slip on a pillow which he also found there.

Presently an officer appeared bearing a tray containing food and drink. Peter, realizing all at once that he was hungry, did full justice to the plain but wholesome fare. Then, feeling utterly wearied with the day’s excitement, waited not for the signal for retiring, but got into bed at once, not forgetting to turn out the light, and fell asleep almost as his head touched the pillow.

II

He was awakened by the loud, clear blast of the morning bugle echoing through the corridor. As he was bathing his face at a lavatory placed in a corner of the room, he heard another bugle note and rapid footsteps on the gallery outside. Going to his door he was soon much interested in watching a long line of boys of about his own age file past, and concluded, from the tumult of steps, sounding from near and far, that all the prisoners must be going to breakfast.

Quite was soon restored, however. The boys ceased to pass his door. The officer brought him his matutinal refreshment. After breakfast he returned to the door and stood for some time, looking out. His cell was so located that he could not see the floor of the corridor, but directly opposite him was one of the great, barred windows, through which he could observe a portion of the paved yard of the prison enclosure and the tall brick buildings bounding its farther side. This was evidently the enclosure through which he had been conveyed the previous evening. Through the open window, sparrows fluttered in and out fearlessly. How he envied them.

Footsteps again in the gallery. A trim liking your officer, tall, and straight as an arrow unlocked the door and bade him follow. Along the gallery they went, down stairs, along corridors, up more stairs, finally joining his associates of the evening before in a large, pleasant room having an inner door communicating with the superintendent’s office.

Clad in uniform of sober fashion black coats, gray trousers, and caps without visors, the group would hardly be recognized as the arrivals of the previous day.

"Wot’s dis for?" Peter finally whispered to a young fellow beside him.

"Don’t know, guess we’re goin’ before de high guy," was the answer. "Say, young feller, if he asks yer if yer can read and write, tell him ‘"no.’"

"Wot’s de use of---"

"Cut out that chinning!" sharply chided the officer in charge. Peter had no further chance to question, but he did not forget the incident.

The door of the superintendent’s office opened. "Consecutive Number 12,345—Luckey—where are you? Oh, there—come into the superintendent’s office;" said a rather good looking boy, clad in a prisoner’s uniform, who came from the inner room.

A little excited, embarrassed, and, if the truth were known, frightened as well, Peter Luckey edged his way from among his fellow prisoners and was conducted through the open door, while the messenger closed behind him.

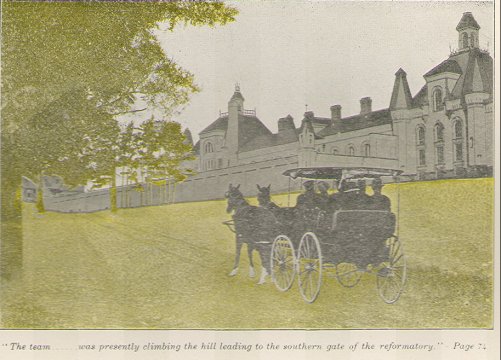

A kindly faced gentleman, sitting at a desk, glanced keenly at him, as he entered. The superintendent, for it was he, motioned the lad to a seat facing him, while he examined for a moment a paper lying upon the desk. Seated at another desk near, was his inmate assistant, a stenographer who had learned the art in the institution. In the window were growing plants. On the walls hung several pictures of elderly, thoughtful looking gentlemen, who, to Peter’s mind, appeared to regard him with distinct disapproval and severity.

The superintendent looked up. "What’s your name, lad?" he crisply demanded.

"Peter Luckey, sir," the boy answered.

"How did you come to be sent here, Peter?"

Peter fumbled with his cap a moment. "Me an’ a feller was workin’ ‘round a power hose on de east side," he finally said; "One night we took some copper wire out of de storeroom. About a week after dat, I guess it was, I was chewin’ wid a feller about sumthin’ and a copy come up and pinched me."

"What became of the wire—did you sell it?"

"No, sir—hid it under a lumber pile near de track—on an empty lot, it was. Me an’ de udder guy had it fixed to go for it and sell it after a while."

"Ever arrested before?"

"Once before."

"How was that?"

"About a year ago, dat was, Boss, I tried to git a bundle out of de back of a wagon."

"What did you get out of that?"

"Not’n. The Judge—Judge Green, it was; he talked to me awahile and let me go.

"What to you do for a living? Did you stay at home?"

"I stayed to me Aunt Kate’s some—not all de time. I staid where I could."

"Are your father and mother dead?"

"Yes, sir, five years ago, I guess; I don’t know exactly when it was. I had to work ‘round at anyting I could git; I worked for two or three mont’s for de power house; I didn’t git much wages."

"Do you drink, smoke, or chew?"

"A glass of beer—with the other boys? You’d take that, wouldn’t you?"

"Yes, sir."

"Luckey, can you add numbers?"

"Add numbers? No, sir, I am very bad at dat."

"How much are fifteen and ten?"

"Fifteen and ten, sir? Twenty-five, sir."

"Can you do multiplication?" "No, sir."

"How much are five times seven?"

"How much? Thirty-five, sir."

"How about division? How many times will five go into twenty?"

"Four times."

"How many times will twenty go in sixty?"

"I can’t tell dat, sir."

"Can you read and write?" "No, sir."

"Pickaxe," said the superintendent, addressing his clerk. "You may put this boy down in arithmetic as far as division."

Have you any disease about you, Luckey?" asked the superintendent.

"Disease? No, sir; I ain’t got no disease."

"What’s your father’s name, Peter?"

"Benjamin Luckey, sir."

"And your mother’s?"

"Elizabeth Greefe, sir."

"Luckey and Greefe! A case of second husband, I suppose.

"No, sir."

"No, How interesting! Third, perhaps?"

"Yes, sir."

"I am inclined to think, Peter, that it runs in your family, and I will venture a guess that you are married, yourself. Is it not so?"

"No sir, I ain’t married nor I don’t want to be."

"So there’s another of my logical inferences gone astray, making an added argument against the theory of heredity, Peter Luckey?"

"Yes, sir."

"Did your father know how to read and write?"

"I don’t know, sir, I don’t tink so."

"Did your mother?"

"Yes, sir, I tink she did."

"Did your father or mother drink?"

"Me fadder got drunk sometimes; me mudder didn’t drink none."

"Have you brothers or sisters, uncles or aunts?"

"No sir, I had an uncle; he lived over in Flatbush; he moved away quite a while ago; I tink he went to New Jersey somewhere; I don’t know where he lives now. I tink it was Passaic he went to; he was a carpenter. Luke Luckey was his name. I hain’t heard from him since he moved away. I got an aunt’ she lived at—18th Street; she’s married; her name is Sugeree—Kate Sugeree. Her man’s a cab driver."

"Have you no other relatives?"

"I dunno of any, sir."

"What is your religious belief, Peter?"

"I dunno, sir."

"Are you a Catholic?"

"No, sir."

"Well, you may go over to the clerk’s desk and sign your name to a paper he will give you, which will authorize me to open any letters which may come here for you; otherwise we shall have to hold the letters here, unopened, until your release from the reformatory."

Peter Luckey went readily enough, and scrawled his name on the paper indiciated. The superintendent smiled.

"Didn’t you tell me you couldn’t write, Peter?"

The boy looked crestfallen.

"I lied to you, sir," he said, "I can read too, a little,"

"Of course you lied, Peter Luckey. Now, don’t do it again; that’s all. Stick to the truth and you will always get on better. You will in due time be assigned to learn a trade here and will also be placed in school. You will likewise be trained in military exercises. In these various departments you will be expected to do your best to learn, and to obey the rules. If you try, there is no reason why you should not get along well, and eventually earn your release. Pickaxe, bringing in 12, 346—Nicholas Settel."

"One night we took some copper wire."

III

In good time the next morning, Luckey was again summoned to join his comrades of the previous day, now gathered in a group in the corridor, outside the physician’s office. Peter’s acquaintance of yesterday, whose name he now knew to be Settel—12,346, sidled up to him.

"Did yer work dat racket?" he whispered behind his band.

"I tried it but it didn’t go. He fooled me before he got troo wid me."

"Dat settles you. Youse’ll get put in a higher class den me and you’ll have to work to get your lessons;--see? You was easy;--see? I fooled him all rite, all rite. I can read and write and figure some. You was dead easy."

Naturally somewhat depressed at his evident lack of mental astuteness, Peter stood, thinking about the matter, when a messenger standing at the doctor’s door, touched his arm; "The doctor is ready for you," he said.

The office of the physician included in its equipment, scales for weighing the prisoner, an appliance by which to ascertain his height, and a printed card, fastened to the wall, for use in testing his eyes.

"Remove your clothes, boy;" briefly directed the doctor, who was seated at his desk; while at another, his clerk waited with a printed from ready placed in his writing machine, on which was to be typed the record of the prisoner’s physical examination.

Presently Peter stepped forth in a state of nature. His weight, and height, together with his name and consecutive number, were ascertained by an assistant, and quickly recorded on the blank form, by the clerk, who then preceded to ask various questions, reading from the printed form before him, and typing the answers thereon as they were given by the prisoner. The questions included inquiries as to the prisoner’s habits regarding the use of alcohol, tobacco, opium, chloral, etc.; likewise questions in reference to his father, mother, sisters and brothers; if living, their state of health; if dead, the cause of death, and the age at death; also as to whether there existed in his family, a record of consumption, insanity, epilepsy, or other hereditary disease. Inquiry was made as to whether the prisoner had ever received a severe injury, and if so, of what nature; and if he had, at that time, any disease, and if so, what were its present symptoms.

"All right, now step over there to the doctor’s desk," said the clerk, briskly.

Peter complied with this request and found himself facing a rosy cheeked young man with a cheerfully gloomy expression who interrogated him as follows:

"Do you ever have any trouble with your heart or lungs, boy?"

"No, sir."

"Draw in deep, full breaths and keep doing it."

The physician took from his table a stethoscope and adjusting the ear-pieces, made a thorough examination of the prisoner’s chest by placing the instrument upon different portions of it. Then, laying the stethoscope aside, and taking a small, rubber-tipped mallet, concluded his examination of the chest by repeatedly tapping upon it with the mallet, interposing his finger in such a manner that the latter received the direct impact of the mallet by being placed over that portion of the chest which the physician desired to test. When he was a length satisfied upon these points, he dictated rapidly to the waiting clerk:

"Heat and lungs, normal."

"Now, my lad, open your mouth—wide." A quick glance at the insite of the mouth; then the doctor queried:

"Can you hear all right?"

"Yes, sir," answered Peter.

"Teeth, poor—hearing, normal, dictated the physician.

"Ever have any trouble with your eyes—can you see good?" was the next question.

"I guess not; I can see pretty good."

"Step over there to the other side of the room—further back—so. Now let me here you read this line of letters."

"L—T—C—P—T, no, F, no L—"

"Put your hand over your right eye," interrupted the doctor. "Now read."

"L—F—O—"

"That’ll do. Put your hand over your left eye. Now try."

"I can’t read that way, sir."

"All right. Eyesight, defective;" was the concluding dictation to the clerk. The record being complete, the prisoner was directed to resume his clothes and take his place with those outside and the next man was summoned.

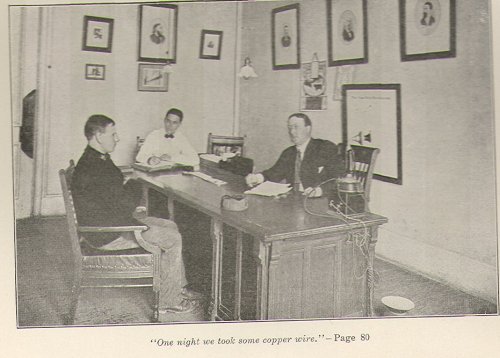

As soon as the doctor had finished with the group, a tall officer with a red mustache arrived, and taking charge of the squad of newcomers, conducted them out of the building in which they were, across the yard, into another building and then, upstairs and upstairs to the top of a high narrow structure where, in a small room, adjoining the photograph gallery, they waited to have their pictures taken and be measured according to the Bertillion identification system.

An inmate barber, whom Peter soon recognized as his hero of the store room, arrived, in charge of a messenger, and was soon busily plying his trade upon one or another of the group. Beyond the barber’s chair, Peter could see the open door of the photograph gallery, with screens placed just inside, so that nothing could be observed of the operations of the photographer. Presently a voice emanated from behind the screen:

"12,345—Luckey!"

"Which is Luckey?" sharply queried the officer with the red mustache. "Oh, that’s you is it? "Come now, be lively and take that coat off. Now fix this around your neck. Here, put this other coat on. Now you look like a dude. Slide in there and get your picture taken!"

Meanwhile, Peter Luckey, divesting himself of his coat, was supplied with a collar and necktie, combined with an adjustable shirt front, all of which were suitably arranged over his regulation shirt. A black coat completed the temporary outfit. These changes served to transform the prisoner, in so far as outward appearance was concerned, into a free citizen again.

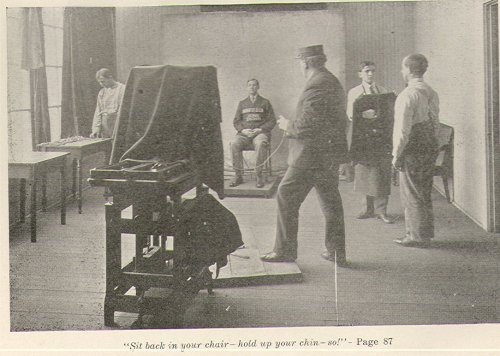

Upon entering the room he was expeditiously placed in a chair standing on a low platform which had a pivot arrangement allowing the occupant to be placed in a position, either facing, or with his side face, turned to the camera. Thus, the photographer, by changing the position of his picture-plate, or negative, was able to obtain both a front and side view of the prisoner with ease and quickness.

"Sit back in your chair—hold up your chin—so!"

As soon as Luckey was seated, an inmate assistant approached him and deftly attached to the front of his coat a stencil, showing his Bertillon letter and number; this, when subsequently photographed with the prisoner, would furnish, in conjunction with the Bertillon measurements afterward obtained and placed on the photograph card, an effectual means of future identification, in the event of his escape from the institution, or of his being wanted by the peace authorities after his release from the reformatory.

The photographer, large and portly, now approached.

"Sit back in your chair—hold up your chin,--so! Get you eyes open and fix them on the camera—steady!—all right. Now stay in the chair. Slater, turn him ‘round. Now, boy, look straight at that spot on the window curtain—steady—all right. Now step down."

"Call the next man;" he continued, handing the negative to an assistant who conveyed it to the "dark room" for development.

Luckey waited outside while the others were being photographed. When Nicholas Settel came back after taking his turn he found an opportunity to say to Peter:

"Gee! De pickchur feller said he’d slap me in the guardhouse if I didn’t cut out me chinnin’—I cut it out—just in time; too! He says: ‘dis ain’t de bowery, young feller!" I guss dat’s right too."

At length the photographing of the group was completed. Then Peter Luckey was again summoned, this time to another room where was arranged the various apparatus for taking the Bertillion measurements and making the examinations incident to same. The measurements included, in addition to his height, the length of the forearm, fingers, feet, ear; and by means of calipers, finely graduated, the measurements of his head were also taken; these included width, distance from ear to top of head, from ear to back of head, etc. He was required to sit in a chair and the distance from chair seat, to crown of head was recorded. By comparison with colored charts conveniently suspended upon the wall, the exact color of different portions of the eye was ascertained. The quality of complexion was likewise noted, together with all peculiar markings of the skin, as moles, scars, tattoos, or any unusual discoloration.

The photographer, who is also the Bertillon measurer, dictated the result of his examination to his inmate Bertillon clerk, the technical nomenclature of the system being readily understood by the latter, who entered same in a book kept for the purpose; the complete data being ultimately printed upon a Bertillon card, containing also the two photographic views of the prisoner, previously taken.

"Now, Luckey," said the measurer, in concluding his examination, "Stand here, on this box." He turned the boy slowly about, scanning him for any additional peculiarities of physique. At length, apparently satisfied, he said with a humorous twinkle of the eye: "Flat-footed. Knock-kneed. Go dress yourself!" and Peter proceeded to resume his garments amid a ripple of laughter from the assistants.

IV

Morning again at the reformatory. Arising betimes, Peter again interested himself in listening to the shrill voice of the bugle and the answering tread of marching feet as the prisoners passed and re-assed his door in the course of the usual morning turnouts. He hoped he would soon be allowed to take his place in the lines and eat with the others, in the dining room. After the prisoners were gone he watched the sparrows awhile. At length the peculiar grating sound of the door brake interrupted his meditations and the officer appeared with his morning meal.

After breakfast he seated himself upon the bed. Noting its tumbled condition, he determined to make it up; this he had neglected to do on the previous day, considering it a matter of minor importance. He then proceeded to set his room generally to rights and was enjoying a consciousness of well doing, novel, but not unpleasant, when the door brake again creaked; footsteps approached, the key was turned, and he was summoned, this time to appear for interview with the director of the trades school.

As he joined the usual group, the loquacious Nicholas, ever ready with advice or suggestion, found an opportunity to whisper:

"A guy told me in de city dat de easier job us here wuz sign paintin’—a cinch, sure ‘nuff, he says. You ask him fer day, see! I’m goin’ to make a stab fer it all rite, all rite."

This sage advice was a seed sown upon good ground. Peter, like most of the class, saw nothing attractive in work. So he instantly resolved to act upon the suggestion of his friend.

The director of trades schools, precise and methodical of appearance, looked judicially at Peter and said:

"Stand a little further over to the right, there, where I can see your face. Now, take your cap off."

Peter was asked a great many questions as to his previous habits of life, occupations, education, etc., the trades school director concluding with the query:

"Well, is there any particular trade you would like to learn while you are here? There are vacancies in"—consulting a printed list of his desk—"in the blacksmithing, bricklaying, and carpentry classes."

The boy, after a suitable pause for contemplation, said:

"I’d like to learn sign paintin’."

The director regarded him with a cynical smile.

"The class is full;" he remarked, curtly, "I conclude, from your description of your former habits, and from my general observation of you, that what you need is good, wholesome manual labor, with the opportunity and necessity for the development of habits of sustained, intelligent effort along prescribed lines requiring not too acute mental processes. I shall therefore recommend your assignment to the bricklaying class. Bring the next man.

Nicholas Settel was called in for interview with the director and returned to his place in the group, without comment.

Peter sidled up to him.

"Wot’d yer git?" he asked with a grin.

What?" Settel looked up absent mindedly. Then, making a wry face:

"Bricklayin’ is what I got. De guy said me dukes looked better hold of a trowel den a razor. I sprung barberin’ on him. I guess he’s on to us, all rite, all rite."

"I wonder who’s de next guy we’ll go before."

"I dunno. Some feller said de school superintendent."

"Bet yer dollar he gits wise to yer spiel same as dis one;" jeeringly remarked Peter.

"Make it ten an’ I’ll take yer;" loftily returned Nicholas Settel.

The sharp reprimand of the officer in charge cut short the conversation.

At length the director of trades school finished his examination of the group, recommending the assignment of each inmate to the trade which in the director’s judgment appeared best suited to the prisoner’s natural ability and the conditions under which he lived, previous to his imprisonment. In the course of the interviews the director dictated from time to time, to his inmate stenographer, data in regard to each man appearing before him, to be in due time properly transcribed and entered upon the records of the trades school office for future reference.

Ten o’clock the next morning found Luckey and his companions in the presence of the school director, a serious looking gentleman with a slight Harvard accent. He directed the prisoners to seat themselves at a long table, and as they were so doing, Luckey noticed that his friend Settel was absent from the group. An inmate assistant distributed writing materials.

"Now, boys," said the school director; "you may each of you write a letter home. Direct your letter to some member of your own family; do not write anyting about getting a pardon; nor anything regarding criminals, nor crime. Just write a good family letter. Tell them about your trip up here; how soon you expect to earn a parole and get home again, and things like that."

Luckey took the pen clumsily, dipped it in the ink and then—a great wave of homesickness swept over him as he tried to collect his thoughts and decide to whom he should write. Intensely desirable seemed the sunny nooks of the east side, and greatly did he long to be back in good old New York!

"Someone entered. Luckey looked up and noticed that it was Settel, just arrived, in charge of an inmate messenger. The school director motioned him to a seat at the table.

"Here, my lad, sit down over on this side. Here are pen, ink and paper. Write a letter home and tell your people how you are. They will be glad to hear from you and after a while you will be allowed to receive a reply from them."

"Mister, I dunno how to"—Nicholas stopped short. In his room that very morning he had been thinking how the baby brother looked at home—little Bobs who had such a cunning way of grabbing the grimy finger of his big brother, wriggling his small legs and gazing up with the most knowing look imaginable on his little round face. Nicholas gave up. He finished his sentence rather lamely:

"Dunno how to ‘rite very good, sir."

"No matter, lad; do as well as you can. We’re none of us perfect writers. Hurry up, now; you came late you know, and some of the boys are through already."

Luckey had been an interested listener. He grinned a little at Nicholas Settel’s boasted plan of causing himself to be placed among the beginners in the school. But he was soon cautioned by the school director to make haste with his writing, and finally decided to write to his Aunt Kate, as being the only relative whose address he knew. Once more dipping his pen in the ink, he scrawled as follows:

"Aunt Kate. i got here all rite, how is de folks in de city, i wish I wuz back dere. i don’t like it very well here,maybe I will like it beter when I am here a wile. some tings aint very bad here. but i am frade i will have to work pretty hard. de boss, says, i, kin git back dere in a year or so. i hope i ken. i wood like to see you and de house and evryting. i guess mabe i will see if i kin git along here, i wish you wood see Shorty and git dat coat i give him and you keep it fur me. Good bye." "Peter Luckey."

Luckey and Settel finished their letters at bout the same time, and were told to join the other prisoners who were by this time seated at the back part of the room.

One by one, the members of the group were summoned to the desk of the school director, for interview. Presently it was Peter’s turn.

"Your name is Peter Luckey?"

"Yes, sir."

"Where were you born and brought up?"

"In New York, sir."

"Never went to school much, did you?" queried the school director, glancing at Peter’s letter which he had selected from the pile before him.

"No, not much; I went a little—not fur four or five year."

"A Protestant school?"

"Yes, sir."

"What have you been doing since you stopped going to school?"

"I done wot I could find to do; I worked for de railroad shops, some."

"I don’t believe you like to work very well, do you?"

"Why, yes, sir, pretty well."

"Did you like to go to school?"

"Yes, sir, I liked dat, but I had ter quit and shift fur meself when me folks died; I forgot most dat I learned den."

"Well, Luckey, most of us have forgotten enough to fill a book. How far did you get when you left school?"

"Not very fure; I could read and write pretty well and figure some. I can multiply numbers and add. I don’t believe I could divide much."

"Did you ever work at anything at which you had to think much—wirte, or add a little, or anything like that?"

"No, sir."

"Could you take up a newspaper and read and understand it?"

"Oh, yes, I could read dat some."

"What paper do you read most?"

"Read most? De Joinal."

"All right, my boy that will do. Go back to your seat."

After interviewing each of the group the school director said: "Now, men, you will begin to go to school soon—on Mondays and Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, the school sessions are held. You will be placed in classes where you will learn something if you try. If you are lazy and don’t work, your school will bother you some. Pay close attention to your teachers, study in your rooms, and you will not have much trouble. Get all you can out of the State of New York, while you are here. Keep the slips which I will give you; they will tell you where to go to school if you forget. If you want a Bible or a prayer book, write me a note and drop it in the box which you will be shown, and I shall receive it and send you the book. You will be allowed other books to read. We want you to read them and get the good out of them. Always keep the book in your room, and keep the card in the book. You may tell the officer in the morning that you want a book. We will send you the first one; after that, you may choose your own.

"I hope that each of you boys will be better able to care for youself when you leave, than you now are.

"Now, when I call your names you may come forward and get what I have for you. 12,345 Luckey."

"Luckey," continued the director; "here is a list of books from which you can select when sending for a library book. Here, also, is a copy of the multiplication table which you had better take with you, to brush up on. Here, too, is a table of American weights and measures which you would best become familiar with. My clerk will presently furnish you with a lead pencil, a couple of pads of paper, and a slate pencil. When you are in the school room a slate will be furnished you to use during the class session; but this is not to be taken to your room. Now you may take your place again."

Each of the group received practically the same articles of school equipment. The school director issued a few additional instructions, and the prisoners, under the charge of a citizen officer, returned to their rooms.

V

"—eight—two—three-four—Left! One—two—three—four, two—two—three--four—Hold!"

"You men in the third squad—watch the guide—watch the guide!" Remember, he is facing you—if he bends to the right, you bend to the left. On the count, move your head to the left—the next count, bring it back to attention—so! One—two! One—two! Do you see?

"Attention! Second series! Hand, wrist and forearm! One—and—two—and—three—and—four--."

Incisive, continuous, it seemed to Peter Luckey that the counting would never leave off. Backward and forward, up and down his limbs moved, in awkward imitation of the precise and graceful movements of the guides. Up and down, backward and forward, till he ached from the unusual motion.

Peter didn’t like the awkward squad; he was very sure of that. The military instructor was too particular; things had to be done just so. Peter wasn’t accustomed to movements of precision, or in fact, precision in any form, and he felt disgruntled and made.

At length the calesthenics, or "setting up" exercises as they were termed, came to an end; hats and coats were resumed and the squad stood at ease.

A messenger came hurriedly into the armory and approaching the military instructor, touched his cap. Receiving the officer’s salute in return, he handed him a slip of paper. The latter glanced at it.

"12,346—Settel—Report here!" commanded the instructor. "Settel;" he continued, when the boy had appeared before him. "God with his messenger. You are wanted at the disciplinary office."

"Sergeant Reilly, the third squad—Wright, the second—Osborne, the first. Reilly, I see you have several brand-new men this morning. Bear, and forbear!" The military instructor walked toward the equipment room.

The new arrivals—twenty or more—were soon hard at work in a remote corner of the armory, while the remaining groups of the awkward squad, graded according to proficiency, were located in other portions of the big room, at sufficient distance from each other to avoid confusion of orders.

Very soon Peter wished with all his heart that he were back again doing "setting up" exercises.

In obedience to an order, the group started to walk a short distance toward the center of the armory. Unfortunate Peter, laboriously painstaking, thrust his right (not in this instance his best) foot forward at the word of command.

"Change shtep—you, there—change shtep! Ain’t ye afther knowin’ yer right fut from yer left? Squard—halt!—Now—you, there—yer left fut forrud at the wurrud "March!" Moind phwat’s goin’ on whin I say ‘Forrud,’ and whin I say ‘March!’ thot means that yer left fut’s to move furst.

"Squad, attention! Forrud—march!"

This time Peter stepped out firmly with his left foot foremost; his zeal out-jumping his discretion, however, he unconsciously lengthened his stride, which soon caused him to stumble against the man ahead, bringing forth another sharp reprimand from his commanding officer. He group marched about thirty feet further when their mediations were interrupted by the sudden order:

"Column left—march!"

"Squad—halt! Phwat koind of marchin’ d’ye call thot?" disgustedly exclaimed Sergeant Reilly, looking daggers at Peter who had "walked around" the corner in his easy, "east side" fashion.

"Why shud ye be afther wearin’ yer shoes out gittin’ ‘round a corner in thot shtyle? Now watch how I do it. Column right—march—one-two-three-four. Column left—march—one-two-three-four. That way—d’ye see? Yes/ all right."

"Squad, attention—Forrud—march!

"Squad—halt! Now men, whin I say ‘Squad,’k ape yer moind on phwat ye’re doin’ an’ whin I say ‘Halt, ye’re to shtop on the scond count afther—this way. Squad, halt—one-two. Squad, halt—one-two.

"Squad, attention! Forrud—march! Hip—hip—hip—hip—"

And so on, seemingly ad infinitum, until the magic hour of eleven-thirty when the hearts of all the awkward squad were gladdened by the signal for dinner.

A hearty dinner did much toward soothing Peter’s ruffled feelings, especially as this was his first meal with the other prisoners, in the general dining room. The food was abundant, and neatly served. On this particular day they had roast beef, potatoes, bread, and coffee. Peter understood that the food would be varied for the different days of the week. He ate his beef from a tin plate; drank his coffee from a tin cup. He had likewise, a steel knife and fork and a pewter spoon, for further aid and comfort in gustatory operations.

He was not allowed to talk aloud, or even whisper, to his neighbors at table. But he had heard that if he behaved well, and strove to make good progress in his school and trade work he might in due time earn the right to eat in another dining room where he could not only to obtain better fare, but enjoy the very desirable privilege of conversing with the others. This, he could see, would make it very fine indeed.

After returning from the armory, the prisoners had been allowed to go to their rooms for a few minutes, in accordance with the usual custom, and wait for the dinner bugle to sound. On his way to the dining room, Peter had observed with interest several big trucks, laden with capacious tin tureens and platters which were being trundled back to the kitchen after discharging their freight of eatables at the dining tables. He met also, several assistants bearing huge tin cans, like water sprinklers, used for serving coffee.

While Peter ate, he watched curiously the long lines of faces, most of them pleasant enough; some of them glum; nearly all of them doing ample justice to the fare. He also noted that the walls looked very white and clean, as did also the tables. He wondered how many there were in the dining room and was just about to ask the man next him when he caught a warning look from the blue coated officer at the end of the table and wisely held his peace.

In half an hour the after dinner bugle sounded. Its note jarred upon Peter. The call seemed not nearly so musical, as had its predecessor. He had eaten his fill; but he did not feel like moving. However, there appeared no other way. So he got up with the others and was soon in the lines, marching toward the shops and the afternoon’s work.

As the lines were passing through the central archway, a sprightly, gray haired old gentleman, in the uniform of a trade instructor, stood near the entrance, giving emphatic instructions to an inmate, apparently one of his assistants, who held a tin pot containing a yellow substance, which looked like varnish. Peter heard a tall young officer, standing by, remark quizzically to a comrade:

"Pop Keuwler’s soap!"

"Sure heath to hogs—don’t touch it!" exclaimed the old gentleman, (who was the institutional soap-maker) turning on the speaker, quick as a flash. Then he walked composedly away with his pupil, leaving the laugh on the joker.

"Fall in line, men!" commanded the officer in charge of the bricklaying class, after the squad had separated itself from the lines and entered the big brick structure, devoted to the use of the bricklayer, stone-cutter, stone-mason, and plasterer classes. These classes are located in different portions of a long room on the ground floor, and are taught by the instructor in bricklaying who is master also of the other trades enumerated.

"Attention to roll call!" continued the officer. He preceeded to check the names of the pupils present, in his book, making a side note of all absentees.

12,345—Luckey—12,346—Settel! Hang up your coats and hats with the rest, over yonder, and then report here at the office," he concluded, after he had finished his checking and consulted a slip of paper just handed him by a messenger.

Peter and Nicholas presently found themselves confronting Mr. Keuwler, who, it appeared, was the instructor in brick-laying.

"I can tell you right here, Mr. Man," he grumbled to the officer having supervision of the class; "I’ve found out just what I’m goin’ to do about that house, there;" pointing to a small brick cottage, about twelve feet high, in process of erection in one corner of the large room. "Now then, just the minute I put one of my good boys on that scaffold to work on that house, Mr. Skeels" (this gentleman was the superintendent of construction) "will be in here and get his eye on that boy workin’ up there and he’ll say to himself, ‘There’s just the man I want for the new trades school buildin’!; Then he’ll ask him his name and number and the first thing I know I haint got no man workin’ up there. Now, then, what I’m going’ to do is to put all my greenies and good for nuthin’s on that scaffold and let Seels have ‘em! See if I don’t."

"Bub," he continued, turning sharply toward Peter; "See that I don’t put you up there! Come—Don’t be standin’ ‘round—you and the other feller get hold of those two trowels, and get over there by that barrel with the mortar board and the green mortar on it. I’ll soon have you throwin’ mortar for three brick. Lively now—lively!"

"Here, give me that trowel!" he went on; after the two boys had taken their places by the barrel and were standing, uncertain what to do next. "Now then, my boys, take a little bit of the mortar—so! Shape it into a nice little pile—this way—then pick it up on your trowel—so—so! And lay it—just like this! Then take and draw the point of your trowel along the middle of the streak and there you are with a nice bed to lay your three brick in. That’s what we call ‘throwin’ for three brick.’ It’s as easy as eatin’! Now let me see you do it."

By this time, the class scattered about the room, singly, or in groups of two or three, were busily engaged, each at his outline or piece of work upon which he was to be examined by the instructor at the expiration of a stated number of hours of labor. The laying of straight wall, building of chimneys, forming of pilasters, "turning" of corners, erection of semi-circular, segmental, dovetail, and Gothic arches—in fact all the work incident to the bricklaying trade appeared to be busily going forward.

Over beyond the bricklayers, could be seen massive sections of foundation wall upon which the stone masons were working. To the right of these, the pupils of the stone cutting class were shaping and finishing the rough blocks of granite and sandstone into the various forms and scrolls prescribed in their trade outlines. Against the opposite wall of the room, a row of small lathed booths, roofed and enclosed upon three sides, were occupied by plasterers who were thus afforded practical experience at their trade.

Some of the bricklayers were at work upon the ornate little cottage, before mentioned. A glance through its open door, revealed a handsome colonial fireplace and mantel, the work of some advanced pupil. An iron crane, and irons, and tongs, a hundred years old, the property of Instructor Keuwler, found space within the arch. Upon the shelves appeared artistic specimens of the stone-cutters’ skill.

A miniature lighthouse, complete, from base to lantern, and about twenty feet in height, could be seen, standing near the instructor’s office.

"Now, then boys," continued the instructor, after watching Peter and Nicholas valiantly strive several times to make the coveted ‘three brick throw,’ "keep right at that till you can do it. You’ll have the class work of three days, or about eight hours, in all, to get so you can do it. Then I’ll come over and examine your work and if you can do it well enough you’ll pass, and if you can’t you won’t. Now keep to work; you’ll have all you want to do; I can tell you that."

"I knew a man in Oswego," continued the instructor, turning to the officer in charge, whom he favored with a slight quiver of an eyelash—"I knew a man in Oswego that many and many a day laid his seven thousand brick. I knew him well. He worked for me for three years and four months. It took five men to ‘tend him. He could make a seven brick throw, easy—easy, sir!"

"Say boss, how’s dis?" asked a youth at work nearby, on a small brick pier.

"How’s that? Why it’s all wrong; that’s how it is! Look at it! Can’t you see?"

"It’s straight, boss; I put the rule on it."

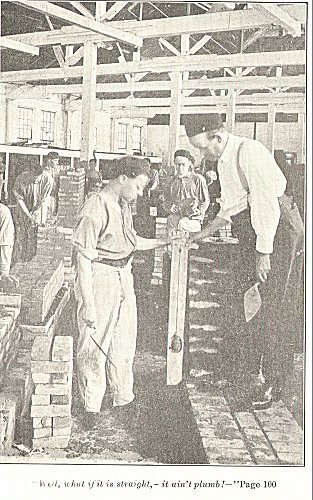

"Well, what if it is straight—it aint plumb—there’s a difference between ‘straight’ and ‘plumb!" Don’t you know that? Why don’t you put your plumb rule down properly—get your line over your mark—there—now you see how plumb it is! You wouldn’t have room enough on a farm to build a barn in, that way."

Bricklaying was numbered among the most practical and useful of the trades taught at the reformatory. While the average pupil would earn his parole before remaining in the class a sufficient period of time to graduate there from, he would still have made sufficient progress to enable him to earn fair wages as an apprentice, after his release. In addition to the class work there was abundant opportunity for intelligent pupils to obtain practical experience at their trade by assignment to the regular construction work almost constantly in progress about the institution.

Ten minutes previous to the expiration of the class period, which lasted from 12:30 until 2:30 p.m., the usual signal to stop work (clapping the hands) was given by the officer in charge. To the two boys it was a very welcome sound, for their arms ached from their labors with the trowel.

Tools were quickly gathered by the inmate instructors, who, after checking their receipt in a book kept for the purpose, locked them in a storeroom near the instructor’s office. The prisoners then gathered at a long sink, supplied with water by individual jets which, continuously flowing, enabled each man to perform his ablutions from running water.

The men were then directed to "pair off;" (one couple preceding another) and the two lines thus formed were carefully counted and compared with the class roll call to make sure that no prisoner had secreted himself in the classroom or elsewhere with the intention of ultimately trying to escape from the reformatory, or, in institutional parlance, attempting to "hideout."

By the time these preparations were completed, the roll of a snare drum signaled for the march to the school rooms, which occupied the entire second and third floors of a large building, located for convenience, adjacent to, and accessible from the northern range of cell blocks.

A wide corridor extended the length of the building, on either floor, from which doors communicated with the numerous class rooms. He partitions separating these rooms from the corridor were largely of glass, rendered partially opaque for a sufficient height to effectually screen the pupils from observation from the corridors. The school rooms also received light from the outside windows of the building, on either side.

Blackboards occupied space upon one wall of each room, from which the floor was terraced, supporting wooden chairs, provided with widened arms, for convenience in writing. A higher chair for the use of the supervising officer was placed in a corner, facing the others. A small table, for the accommodation of the inmate instructor, stood in front of the blackboard. In the windows were boxes of flowering and foliage plants.

In due time the lines entered the school building and, traversing the lower corridor, ascended the stairs at the further end and moved along the upper hall; the pupils leaving the ranks upon arriving at their proper class rooms, which were easily identified by the numbers over the doors.

It was quite an animated scene—messengers hurrying to and fro; prisoner pupils locating and entering the school rooms to which they had been assigned; inmate instructors receiving from the school director the roll call books for the different classes, then ranging themselves in line in the corridor to wait for the signal to enter upon their duties as teachers. Stationed along the corridors were citizen supervising officers. Others, assigned to duty in the class room were already in their chairs; one or two late comers were just arriving.

Luckey and Settel, entering with the rest of the prisoners, and not knowing exactly where to go, very naturally became stranded, in company with a half-dozen of the other new men, at the further end of the upper corridor. Standing near them was the officer with the red mustache who had conducted the party to the photograph gallery.

"I see yer leave de squad, dis mornin’ wid de messenger guy. Where’d he take yer?" asked Peter of Nicolas as the two stood together by the window.

"My eye!—but dat was a close one!" remarked the latter. "De guy in the office wanted to know where I got a little bit o’ ‘baccy dey found in de cubberd. I says to ‘im, I says: ‘A feller trun it in de do’ when he wus goin’ by,’ I says: Oh, dat’s straight goods—dat’s wot he dun. Den de guy he says:

‘You’re one of the new men, I see by your number,’ he says: and I says ‘Yes’; and den he looks at me hard and he says; ‘Of course you din’t take a chew of dis?’ an’ he hel’ up de plug wid de marks on it of bein’ half bit off.

‘I didn’t take a single chew off it!’ I says lookin’ him straight in de ye.

‘How about half-a-dozen?’ he says, wid a wink.

‘I dunno as I’m exactly prepared to say as to dat.’ I says: Hully gee, Cully, but I’d soit’nly filled me face wid dat ‘baccy ‘bout ‘leven or twenty times, all right, all right—Hully gee, but it tasted good! Don’t yer—

"Now, look here, you, Settel! This is the second time I’ve caught you chinning with him. Here’s where you both get a yellow out it—what’s your number?"

"Oh, say boss, I wuz—

"What’s your number! Don’t give me any game of talk—I know what you did—talking calls for a second class report and you’ll get it—what’s your number?"

"Now, you fellows, pair off and stand at attention—I’ve heard enough of you!" concluded the officer, as he recorded in his book, the respective names and consecutive numbers of Nicholas Settel and Peter Luckey, tremblingly given by these unfortunate individuals.

A few minutes latter, the boys saw the school director approaching.

"All right, captain, I’ll take these men now;" he remarked to the officer. "Come, boys, and I’ll show you where you are to go to school."

Proceeding along the upper corridor, followed by the group of newcomers, the school director conducted them all to school room number twenty-three.

"Here are six men for you, Lane;" he said to the inmate instructor who was engaged in placing some written work upon the black board, preparatory to beginning work with his class, "you can talk to them a little before roll call, can’t you?"

"New men?" Certainly Mr. Upton; I’ve got my work all in shape now. Say, Mr. Upton, I haven’t got my late light permit yet. I’ve been in the normal class two weeks now. I wish I had it. I don’t have half enough time to prepare my work. Will you see about that, Mr. Upton?"

"All right, Lane; I’ll take that up with the guard room office. You don’t look overworked though. You’re sure you don’t want that late light to read your library book by, are you? Yes? All right, I’ll see about it. Get after these men now." The school director went out.

The instructor, a bright appearing youth, about nineteen years of age, greeted the new arrivals pleasantly and gave them seats in the front row of chairs. After asking them some questions about their previous school advantages, he said:

"To-day being Thursday, we study language—the classes in language occur on Thursdays and Fridays, and arithmetic, on Mondays and Tuesdays. This afternoon we are going to have some reading and also some spelling—writing words on your pads. If you attend closely to what is going on you will soon be able to work with the class. You will be given something to take to your rooms and prepare for the next class recitation. If you study in your rooms you will get along a good deal better in your classes. Our work here is not so very hard but you will have to do some thinking, which won’t hurt any of you. Once a month you’ll be examined, to see what you have learned during the month. You must pass these examinations or it will cost you money—I suppose you know that? Anything under seventy-five percent, and over fifty will cost you a dollar; under fifty and over twenty-five, two dollars; anything under twenty-five percent, will cost you three dollars. I suppose that you know that you are working for the State, here, for about fifteen cents a day and your board, don’t you, and that if you get in debt by failing in your examinations, it will hinder your getting out of here just so much—there’s a point there, you sell, all right? S is up to you fellows to ‘saw wood,’ or get left."

"Say, boss, I don’t git dat troo me nut—de guy in de mil’t’ry said sumthin’ but I didn’t ketch on none. I don’t wanta stay here longer’n I hav’ ter," said Peter Luckey with decision.

"New me!" briefly added Nicholas Settel.

"You’ve a rule book, haven’t you? Why don’t you read it?" asked the instructor.

"I hain’t had no—Oh, gee—dat’s so; a guy in de office giv us all a little book when we went out; after de high guy—

"Say, ‘superintendent’—that’s his name—the ‘general superintendent’. You’re liable to get yourself disliked if you call the officials here, ‘guys’; I don’t mind telling you that."

"I didn’t mean nuthin’, sir" said Peter.

"All right. Now if you have received a rule book, I give you a straight tip that you had better study it through in your room to-night. You;ll find it’ll be good for what ails you. Now sit up and take notice, boys, and do as you’re told." Concluded the instructor, as he arose and took his position in front of the class.

"Last week," he said, I gave each of you five slips of paper cut in the form of an envelope, and asked that you write a different address upon each one, in the proper form. Three of these were to contain titles, and all, the abbreviation for the name of a State. How many have done this?"

All raised their hands, with the exception of the new pupils.

"You were also given a printed outline, containing eight incomplete sentences, the information for the filling of the spaces, to be supplied in writing, by yourselves. Has this been done? Yes? All right; Moriarty, please collect the slips and place them on the table here."

The instructor glanced casually at several of the slips as they were handed in. Then he smiled.

"One of these sentences you have all seemed to end the same way. Are you sure you haven’t communicated? This sentence: ‘On next Fourth of July I should like to visit’—and then you’ve all written, ‘New York!" I wonder how that happened!"

The instructor then proceeded to distribute certain printed slips containing the description of the building of the canoe, from Longfellow’s beautiful poem, "Hiawatha." Sentence by sentence, this was read by the class. Some little time had, no doubt, been devoted to the study of this selection as, upon request, several pupils repeated portions of it from memory, with good expression. When a bright young fellow, the star of the class, recited the last few lines, beginning:

"Thus the birch canoe was builded

In the valley by the river,

In the bosom of the forest."…..

Our friend Peter was mightily impressed and fervently wished he could do as well.

After the reading of the poem, the instructor indicated with his pointer, a list of words, selected from the piece just read, which he had previously written on the board. These words he now gave out to different members of the class with the request that each make a sentence which should include the word given.

Peter Luckey was among the pupils thus honored, and instantly realized that he was, to use his own expression, "up agin it." His word was "water" and to save his life he could think of nothing to say about it; especially after listening to the flowery sentences in due time given forth by more practiced, or perchance more gifted scholars. Particularly did he feel overshadowed by the genius of the bright youth who had last recited from "Hiawatha," and who had received the apparently unpromising word "resin" and had almost immediately sprang to his feet and recited: "The resin on the bow makes the violin string sing." However, after waiting until the last minute, Peter had had an inspiration and won the deserved applause of teacher and pupils by enunciating the sterling epigram, "Water is better than whiskey!"

VI

Peter Luckey languished in the guard house. Melancholy was written large all over him. For the space of two days he had done little but restlessly pace the narrow cell. Two nights "devoid of ease" had he slept upon a mattress, placed upon the chilly, unsympathetic stone floor—no bedstead, no pillow, no chair nor table. His own room appeared by comparison, luxurious, to a degree.

The story of Peter’s transgression is not so very long in the telling—a single blow; "only that and nothing more"—and here he was, in disgrace—and discomfort! Ten months had now elapsed since his reception at the reformatory; ten months in which he had run well. Quite a bit of patient study of his rule book, nights, eked out with bits of information gleaned here and there, and close observation of the ways of the other prisoners, sufficed to soon render him tolerably familiar with the institutional routine. He had had good sense enough to see where the "shoe pinched," and resolved to make an effort to earn his release by parole. This, he found would take about thirteen months, provided he did not make any slips. His "chinning" with Nicholas, in the corridor of the school rooms, for which misdemeanor, Captain Reeves had given each of the boys a "yellow," or second class report, meant a fine of twenty-five cents—not a large amount, but still sufficient to indicate in which direction the wind set, and to serve as a warning against future and possibly more serious infractions of the reformatory discipline.

His task in the school of letters, though requiring considerable class and evening study, he had managed to get through with, in a fairly satisfactory manner thus far. Although suffering several failures in examination, no one of these had merited more than a dollar fine. His spelling was one of his weak points, but this had greatly improved of late.

In his trade, bricklaying, he took great interest, and learned rapidly. In this work he was examined at the expiration of an allotted number of hours of practice, and as yet he had not failed in a single routine.

He had experienced a hard siege with Sergeant Reilly and the awkward squad, but finally graduated, in seven weeks, and now proudly appeared with the regiment, at dress parade, on Wednesday and Saturdays. Peter was a very good natured boy and had become quite a favorite among the prisoners with whom the routine necessitated his coming in contact. Two or three months previous, he had gained promotion to the first, or highest institutional grade and had begun to anticipate the day when he should be summoned to appear before the august body, the board of managers, and be authorized for parole!

And now, as stated above, Peter languished in the guard house. To particularize: Peter had an enemy. The feud was ancient, of "east side" origin, in fact—something touching the insulted honor of "de gang," or perchance, "de odder bunch"—a vital point, without doubt. Peter’s emeny’s name was Dogan. He had a red head and a squint in his eye. Peter’s hair was also red.

Dogan had long been absent from the twilight councils of his "gang" and it developed that he had been persuaded to pass the interim in the "College on the Hill," on account of a penchant for climbing balcony pillars.

Peter recognized Dogan the second day after the former’s assignment to the bricklaying class. Dogan favored Peter with a truculent smile. Time passed on. Peter for a time had not much trouble in avoiding his old time adversary, as Dogan had been along time in the class and was quite a bit in advance of Peter and consequently located in a different portion of the room. However, as before mentioned the latter soon became greatly interested in his trade and, passing every outline, in due time, overtook Dogan, who was a lazy, mischievous boy and had, in the course of his institutional career, passed two months in the "Wing" a splace in the reformatory where they darned socks and mended clothes, in depressing silence, from morn till eve. Moreover, Dogan cared little, whether or not he passed his trade outlines, as he had fully determined to do his "bit" of two and one-half years; and he had hinted, so Peter heard, that he, Peter Luckey, should not miss a like experience if he, Dogan, could compass it.

So in due time, destiny and the trades school office decreed that Peter and Dogan should share the same mortar board, although engaged upon different work: Dogan being still one outline in advance.

One day office Dale paused a moment in passing;

"Well, Luckey, come out of your trance and get in the game awhile! What’s the matter? You look as if you’d seen a ghost!"

Peter started. He had been lost in contemplation of the particular spot where he had placed his trowel a moment before, in order to pile over some bricks, and had not noticed the approach of the officer.

"Boss, I can’t find me"—

"Lost your what?—trowel? Why man look! It’s right there behind you!"

"Boss, I looked dere just a second ago—dat ain’t where I laid it down either.

"Oh, I guess it was; you were dreaming," said the officer. "Dogan," he continued, after a moment; "you’re terribly industrious this afternoon—I hope it’ll last!" and the officer passed on.,

"T’other red-head hid yer trowel—I saw him put it back;" remarked a tall, lean youth to Peter, in a low tone, as the former trundled a wheelbarrow past, on his way to the mortar bed.