|

| The History Center on Main Street, 83 N. Main Street, Mansfield PA 16933 histcent83@gmail.com |

|

|

|

Cayuga County - Site of Destroyed Indian Villages |

|

|

Reprinted with gratitude and the permission of James Towner, Publisher.

Transcribed by: Richard J. McCracken, Towanda, Pa., October 2001

Between 1776 and 1779, the War for Independence was not going well for the Continental Army. Inadequately funded, clothed, equipped and fed, the army was severely demoralized. It endured unimaginable hardships at times and places such as the winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge and Trenton. Sympathetic colonist living on the northern frontier suffered numerous raids upon their homes by bands of Indians, Tories and British Rangers equipped and led by Major James Butler, operating from the British strongholds at Fort Niagara and the Finger Lakes region of New York. Many of the pioneers lost their lives or were taken captive in these raids. In July 1778, the colonists suffered the bloodiest loss of life of the war near Wilkes-Barre, Pa., at the Battle of Wyoming and the concurrent Wyoming Massacre. Colonel Thomas Hartley’s scouting expedition in September 1778, followed by Major General John Sullivan’s punitive campaign in 1779, broke the effectiveness of the alliance between British and Iroquois. Following Sullivan’s foray into and through Bradford and Chemung Counties, the Iroquois and the British of Canada and Niagara were never again a significant factor in the affairs of the nascent Republic. Although few Iroquoian lives were lost as a result of Sullivan’s campaign, the near total destruction of their communities and food sources in the lands between Wyoming and the Canadian border, from Albany to Niagara, forced the Indians to gather at and rely upon Fort Niagara for sustenance. Camped at the fort, they were soon decimated by famine and disease, which took thousands of their lives; they thereafter became dependant upon Europeans for their existence.

The following two articles were published in The Sunday Review, Towanda, Pa., between 8 July and 26 August 2001. The first, printed on 8 July 2001, is an overview of Maj. Gen. John Sullivan’s campaign against the British forces of Maj. James Butler and his Indian allies, under war chief Capt. Joseph Brandt, the Six Nation Iroquois of the Finger Lakes region of New York State. The second article is a six-part series printed between 29 July and 26 August 2001, detailing Gen. Sullivan’s activities in Bradford County, Pa. and Chemung County, N.Y.

The articles are gratefully reproduced here with permission of James Towner, Publisher of The Daily and The Sunday Reviews of Bradford-Sullivan Counties, Pa.

Author and Review staff writer Kevin Olmstead, states that the primary source of his research data is the journal of Lt. Col. Adam Hubley of Gen. Maxwell Hand’s Light Corps. The transcriber has added the footnotes.

¾ Richard J. McCracken, Towanda, Pa; October 2001

Sullivan’s March a Turning Point in the Revolutionary War

8 July 2001

Two-hundred twenty-five years ago this weekend, the British were hopping mad.

Days earlier, the scruffy, tearaway colonies had just had the audacity to declare their independence of the crown.

Of course, this meant war – though probably not much of one. Surely, the rag-tag colonists could not match up to what was arguably the most powerful military force in the world at the time – Great Britain.

At the same time, the people of the six Iroquois nations – the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk and Tuscarora – were a little miffed that colonists were encroaching into their territory, which consisted of roughly the Allegheny, Genesee, Upper Susquehanna and Chemung River basins, plus the Finger Lakes.

The Iroquois nations allied themselves with the British and went about terrorizing the American settlements in the region.

For three years the British – including colonial Tories who remained loyal to the crown – and Colonial armies fought tooth-and-nail. Meanwhile, the Iroquois raided colonial villages in Western New York and along the Susquehanna. The raids struck fear into the settlers; indeed, it was well-known that much of the land in the Chemung Valley was unsafe for white settlers to tread into.

The raids left the colonists demoralized, but angry. They were hungry for retaliation.

In the summer of 1779, the main colonial army was for the most part inactive, camped out near the Hudson River in New York.

Meanwhile, Colonial Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, with the support of French Admiral Comte D’Estaing’s fleet, attempted in vain to lay siege on Savannah. The French had declared war on Britain the previous year, and Lincoln and South Carolina Gov. John Rutledge believed they would be the only hope for saving South Carolina and Georgia. Benjamin Franklin himself made trips to France to gain the support of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

While the British were kept busy in the southern colonies by colonists with French assistance – and by the French themselves around the globe – Gen. George Washington decided it was time to strike a decisive blow against the Iroquois.

He ordered Daniel Broadhead to lead an army from Fort Pitt (modern-day Pittsburgh) up the Allegheny River. He also ordered Gen. James Clinton to lead an army up the Hudson and Mohawk valleys. He sent a larger army, under Gen. John Sullivan, from Wyoming up the Susquehanna Valley to the Finger Lakes.

The armies were ordered to "destroy all Indian villages and crops belonging to the six nations, to engage the Indian and Tory marauders under Brandt and Butler whenever possible, and to drive them so far west that future raids would be impossible."

After the destruction of the Iroquois villages, the armies were to combine and attack the British stronghold at Fort Niagara. Sullivan embarked from Wyoming July 31, 1779. His men marched toward Tioga Point (modern-day Athens). On Aug. 5, the army "descended the mountain nearly one mile in length, and arrived in a fine and large valley, known by the name of Wyalusing."

The area had been settled by Indians and white people together, but the settlement had been destroyed after the war started. By the time Sullivan arrived, it was primarily a large meadow.

The army camped at Wyalusing and waited the next day for boats to arrive on the Susquehanna. The boats did not arrive until late in the day. Rain moved into the area that night, hindering the army’s movement until Aug. 8.

After crossing Wyalusing Creek, the army camped along the river near Wesauking Creek, where some of Sullivan’s officers discovered a small, unoccupied Indian village. The boats, however, were not able to reach Wesauking and encamped at Standing Stone.

The next day, the army arrived at "Sheshecununk," where it appeared to have just missed a group of Indians. Scouts noted fresh tracks, fresh boughs cut and evidence of a recent fire in the area.

The Army arrived at Tioga Point on Aug. 11. Soldiers set up camp at a point 2 ½ miles from the confluence of the "Tioga Branch" (Chemung River) and the Susquehanna. At the chosen point, the two rivers were 190 yards apart, Sullivan reported in his diary.

A garrison was stationed at Tioga Point to cover the western army. Meanwhile, a scout of eight men was sent up the Tioga Branch to investigate the Chemung area.

The scout returned the next day, having made several discoveries. The men told of an Indian village 12 miles away where a council of war sat.

The Army was ordered up the Tioga Branch to engage the Iroquois.

Gen. Edward hand’s brigade led the march, flanked by the brigades of Gens. Enoch Poor and William Maxwell.

The morning of Aug. 13 was foggy, which Sullivan said was favorable for the Army’s mission. After having some difficulty finding the town, Hand’s brigade found a few vacated huts. An hour later, Sullivan’s army came upon the main town.

Sullivan ordered two regiments across the river to head off a potential escape route for the Indians. Sullivan ordered the remainder of the army to raid the town.

The town fell rather easily at about 5 a.m., considering it had already been abandoned.

Sullivan reasoned that the Iroquois had discovered the scouting party the previous day and evacuated the town.

As troops investigated the town, Hand led the light infantry company on the path about a mile from the town. There, Capt. Bush, under Hand’s commend, discovered a fire burning and a sleeping Indian dog.

"With a degree of tepidity seldom to be met," Sullivan ordered the army up the path.

As the soldiers marched up the path, which led to the Indian settlement of Newtown, some as-yet-undiscovered Iroquois hiding atop a high hill to their east fired upon them. Sullivan’s regiment pushed up the hill as Bush led a regiment to the rear of the Iroquois position. However, the Indians were able to escape, carrying off their wounded and killed, as prescribed by their custom.

Six Army soldiers were killed and 12 injured in the Chemung Ambush.

The Army took control of the summit of the hill.

Sullivan ordered the Army to cross the river and destroy some substantial fields of Iroquois crops, including corn and beans. While doing so, the brigades of Poor and Maxwell were fired upon by Iroquois. One soldier was killed, and several more soldiers were injured.

After the fields were burned, the Army returned to Chemung, and eventually to Tioga Point, where the dead were interred.

On Aug. 16, Poor’s brigade was sent up the Susquehanna to join with Clinton’s army, which had cut south from the Mohawk settlements through the Otsego and upper Susquehanna valleys.

On Aug. 22, Poor and Clinton joined Sullivan’s army at Fort Sullivan, as the army settlement at Tioga Point was called.

Four days later, nearly 5,000 men left Tioga Point and traveled up the "Tioga Branch" again, bound for Newtown.

The weather did not cooperate. Rain swelled the Chemung River and the army was additionally hampered by treacherous terrain. Some refugee Tories joined the Colonial army at Chemung.

The army arrived in Newtown Aug. 29. And the Iroquois were prepared.

They had set up another ambush, concealed by freshly cut saplings, along an old Indian trail. At the point of ambush, the army would be surrounded by Baldwin Creek, an extensive swamp, a high hill and British forces hiding in a wooded ridge along the trail.

Sullivan’s scouts discovered the ambush, however, allowing Sullivan to devise a counter-attack. He sent Col. Ogden to the west, along the Chemung River, and Clinton and Poor to the east, through the swamp and to the base of the hill.

When all was set, the Colonials started firing artillery at the Indians and the plan was set into action.

The swamp slowed Poor and Clinton, but it could not stop them. They eventually gained higher ground and engaged the Indians and Tories, who retreated across the river and into the hills after a hotly-contested battle, which left three Colonials dead and 36 wounded. The dead were interred at Tioga Point and the wounded were sent back there for treatment.

Twelve enemy soldiers were found slain, with two prisoners taken. The Iroquois carried off their wounded.

Before the autumn would set in, Sullivan’s army would venture up the Chemung River, then up Catherine Creek to Seneca Lake in New York. The Army, with the help of some Oneidas later in the campaign, destroyed the Seneca and Cayuga villages of the Finger Lakes and Genesee Valley, including the settlement of Genesee, regarded as the capital settlement of the Seneca.

However, the main objective was not achieved. Clinton and Sullivan never met up with Broadhead, and with winter fast approaching, Sullivan though it too risky to continue to Fort Niagara to take on a well-equipped British Army.

The expedition proved to be a successful one for many reasons. The Iroquois were all but taken out of the war; in fact, the six nations never again fought as a confederacy. Their confidence in their British allies was lost, having seen their families killed and homes and crops destroyed. The destroyed crops deprived the British of a critical supply of food.

The campaign also foiled an attack from Fort Niagara, and gave the Colonial army a shot in the arm. Colonists were no longer disillusioned.

Probably most importantly, it also opened up the west for the Colonies, giving them room to grow after the war was eventually won. It was the beginning of over two centuries of growth.

Editor’s Note: All quotes are taken from Lt. Col Adam Hubley’s Journal,

1779.

Sullivan’s March Began 222 Years Ago This Week

29 July 2001

Two-hundred twenty-two years ago, colonial settlers were not in good shape.

The Army was struggling against the British. Meanwhile, Iroquois warriors were routinely raiding colonial settlements in the Susquehanna Valley and what is today Western New York.

With the British also at war with the French and fighting them all over the world, members of the Continental Congress decided it was time for some retaliation.

From his headquarters in Easton, Gen. George Washington ordered Daniel Broadhead to march from Fort Pitt up the Allegheny River. A larger army, led by Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, would march from Wyoming, near modern-day Wilkes-Barre, to the Finger Lakes area of New York. Along the way, they were to destroy all Iroquois villages and crops and engage the warriors and British troops whenever possible.

Sullivan’s army included light corps, commanded by Gen. Edward Hand; and brigades commanded by Gens. William Maxwell and Enoch Poor.

Another brigade, led by Gen. James Clinton would march from the Hudson valley, up the Mohawk Valley, through the headwaters of the Susquehanna and along that river to Tioga Point (modern-day Athens), where it would join Sullivan’s army.

According to the Order of March, "the light corps will advance by the right of companies in files, and keep at least one mile in front,, Maxwell’s brigade will advance by its right in files, sections, or platoons, as the country will admit. Poor’s brigade will advance by its left in the same manner. Clinton’s brigade will advance by the right of regiment, in platoons, files, or sections, as the country will admit. All the covering parties and flanking divisions on the right will advance by their left; those on the left of the army will advance by their right. The artillery and pack horses are to march in the center."

Hand’s light corps included Pennsylvania’s 11th volunteers, led by Lt. Col. Adam Hubley. The following accounts of the march are based on his journal.

Wyoming – July 30, 1779

Hubley noted that Wyoming, situated on the east side of the east branch of the Susquehanna, consisted of about 70 houses – chiefly log buildings, with sundry larger buildings and a small fort erected by the army. There was also a small shelter for the inhabitants in case of alarm.

The fort was garrisoned by 100 men, drafted from the western army, and put under the command of Col. Zebulon Butler.

Hubley noted that the inhabitants of Wyoming were not in good shape.

"Two-thirds of them are widows and orphans, who, by the vile hands of the savages, have not only (been) deprived some of the tender husbands, some of indulgent parents, and others of affectionate friends and acquaintances, besides robbed and plundered of all their furniture and clothing. In short, they are left totally dependent on the public, and are become absolute objects of charity," Hubley wrote.

He described the surroundings.

"The situation of this place is elegant and delightful," he wrote. "It composes an extensive valley, bounded both on the east and west side of the river by large chains of mountains. The valley, a mere garden of an excellent rich soil, abounding with large timber or all kinds, and through the center the east branch of the Susquehanna."

Wyoming – July 31, 1779

Sullivan officially began the march to Tioga Point.

Hubley noted that the army embarked at about 1 p.m.

"Light corps advanced in front of main body about a mile," Hubley wrote. "Vanguard, consisting of twenty-four men, under command of a subaltern, and Poor’s brigade, (main body), followed by pack horses and cattle, after which, one complete regiment, taken alternately from Maxwell’s and Poor’s brigades.

Hubley noted that the terrain was broken and mountainous, wooded with low pines. He saw evidence of some of the raids.

"I was struck on this day’s march with the ruins of many houses, chiefly built of logs, and uninhabited; though poor, yet happy in their situation, until that horrid engagement, when the British tyrant let loose upon them his emissaries, the savages of the wood, who not only destroyed and laid waste those cottages, but in cool blood massacred and cut off the inhabitants, not even sparing gray locks of helpless infancy," Hubley wrote.

At about 4 p.m., the army arrived at Lackawana, which Hubley described as "a most beautiful plain, covered with an abundance of grass."

He wrote that the soil was excessively rich, and a delightful stream of water – the Lackawana – flowed through the plain.

The Army crossed the stream and encamped about one mile north of it. It began raining that night. The rain continued until morning.

Lackawana – Aug 1, 1779

The Army was detained until noon. The rain of the previous night created considerable rapids, which slowed the fleet. In fact, the Army lost two boats, though much of the cargo was saved.

The fleet caught up to the Army at about 2 p.m. The army then moved. About one mile from the encampment, the Army entered the narrows on the river. One detachment was sent to cross the mountain, which was almost inaccessible, "in order to cover the army from falling in an ambuscade."

Hubley noted that passage through the narrows was extremely difficult due to the poor path.

The army passed by Spring Falls.

"To attempt a description of it would be almost presumption," Hubley wrote. "Let this short account thereof suffice. The first or upper fall thereof is nearly 90 feet perpendicular, pouring from a solid rock, uttering forth a most beautiful echo, and is received by a cleft of rocks considerably more projected than the former, from whence it rolls gradually and empties into the Susquehanna."

By 6 p.m., the light corps passed through the narrows. At about dusk, it arrived at a place called Quilitimunk.

"Quilitimunk is a spot of ground situate on the river; fine, open and clear; quantity, about 1200 acres; soil very rich, timber fine, grass in abundance, and contains several exceedingly fine springs," Hubley wrote.

The Army encamped one mile in front of the place. The difficult passage meant many soldiers marched nearly all night before arriving at camp. Much baggage was dropped and left lying along the way.

Quilutimunk – Aug 2, 1779

The Army was ordered to remain here due to the difficult and tedious march the preceding day. It prepared to march the following day with five days’ provision.

"Nothing material happened during our stay on this ground," Hubley wrote.

Quilutimunk – Aug 3, 1779

The Army marched at 6 a.m. Hubley noted that the mountains were exceedingly level for at least six miles. The timber consisted of pine and white oak.

"About three miles from Quilutimunk, we crossed near another cataract, which descended the mountain in three successive falls, the least of which is equal if not superior to the one already described," Hubley wrote. "Although it is not quite so high, it is much wider, and likewise empties into the Susquehanna, seemingly white as milk. They are commonly known by the name of Buttermilk Falls."

At about midday, the Army descended the mountains near the river, marched about a mile on a flat piece of land, and arrived at a stream known as Tunkhannunk.

The Army crossed the stream and encamped along the river at about 1 p.m.

"Nothing material happened this day excepting a discovery of two Indians by the party on the west side of the river," Hubley wrote. "Indians finding themselves rather near the party were obliged to leave their canoe, and make through the mountains."

The party took possession of the canoe and camped across the river from the main army.

Tunkhannununk – Aug 4, 1776

The Army embarked at 5 a.m., moving three miles up the river close under an almost inaccessible mountain. It then ascended the mountain, with great difficulty, and continued on it for nearly seven miles.

"A considerable distance from the river, the path along the mountain was exceedingly rough, and carried through several very considerable swamps, in which were large morasses," Hubley wrote. "The land in general thin and broken, abounds in wild deer and other game. We then descended the mountain, and at the foot of it, crossed a small creek called Massasppi, immediately where it empties into the river."

On a fine, clear, very hot day, the Army continued up the Massasppi until reaching Vanderlip’s farm, where it discovered several old Indian encampments. One of them appeared to have been very large.

"The land, after crossing Massasppi, was exceedingly fine and rich, the soil very black and well timbered, chiefly with black walnut, which are remarkably large, some not less than six feet over, and excessively high." Hubley wrote. "It is likewise well-calculated for making fine and extensive meadows."

At about 1 p.m., the main army encamped at Vanderlip’s farm, and the infantry advanced about one mile higher up on a place know by the name of Williamson’s farm.

Editor’s Note: This series will continue next Sunday.

Sullivan’s Army Reached Bradford County 222 Years Ago This Week

5 August 2001

During this week, 222 years ago, Gen. John Sullivan led his army through Bradford County.

The army had left the previous week from Wyoming with orders to march up the Susquehanna Valley and into the Finger Lakes area. Soldiers were to destroy any crops and villages of the six Iroquois nations and engage any Iroquois or British soldiers they found along the way in retaliation for Iroquois raids on colonial settlements.

The following accounts are from the journal of Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, who was a member of the light corps under Gen. Maxwell Hand.

Massasppi – Aug. 5, 1779

The army was ordered to march at 5 a.m., but the boats were impeded by the rapidness of the water below the camp and could not reach the army. The boats finally caught up at about 9 a.m., at which time the entire army halted.

According to Hubley, the entire army moved out on this clear and very warm day, but encountered more danger than it had before.

The right and left columns of the light corps, conducted by Gen. Hand, moved along the top of a very high mountain. Hubley commanded the main body of the light corps, with an advance of twenty-four men. They moved several miles along the edge of the river. The main army, flanked on its right by four hundred men, also moved over the mountain.

"Thus we moved for several miles, then arrived in a small valley called Depue’s farm; the land very good," Hubley wrote.

Hubley noted that this was the area in which Col. Hartley was attacked by Iroquois warriors in 1778 as he was returning to Wyoming from Tioga. He wrote that both sides had taken losses in the skirmish, but the Iroquois eventually gave way and Hartley was able to return to Wyoming without further trouble.

The army continued its march for about a mile before rejoining with the parties on the right flank. Together, they ascended a high mountain, and marched for several miles.

"Land poor, timber but small, chiefly pine," Hubley wrote.

Soon, the army descended the mountain, a length of nearly one mile, and "arrived in a fine and large valley, known by the name of Wyalusing."

The main army camped out at Wyalusing. The infantry advanced about one mile and encamped at about 2 p.m.

Wyalusing – Aug. 6, 1779

Once again, the boats lagged behind in the river. The army was ordered to remain at Wyalusing and march early the following morning.

Soldiers used the day to prepare three-days provision and get their arms and accoutrements in perfect order before the next day’s march.

Twenty-four of Hubley’s men went on a reconnaissance mission in the vicinity of the camp. They returned in the evening without having discovered evidence of Iroquois presence nearby.

The boats arrived late in the day.

Rain also set in on the area that evening and continued through the night.

Wyalusing – Aug. 7, 1779

Rain continued through the night and into the morning, making the army’s planned march impossible.

According to Hubley, the army was ordered to remain camped out in Wyalusing until it receives further orders.

With nothing else to do, some of Hubley’s men went on a scouting mission.

"A captain and thirty men from my regiment reconnoitered vicinity of camp; made no discoveries," Hubley wrote.

However, the day did not pass without the soldiers receiving news from higher up.

"This day received a letter (by express) from his Excellency Gen. Washington, dated Head Quarters, at New Windsor," Hubley wrote. He did not elaborate on the contents of the letter.

Wyalusing – Aug. 8, 1779

Finally, the army moved out at 5 a.m.

In the same order as a few days earlier, the army crossed Wyalusing Creek and ascended an "extensive mountain." Hubley reported that the land was poor, with small timber.

The inclement weather left Gen. Sullivan feeling unwell. He traveled on a boat.

At about 10 a.m., the army arrived at the north end of the mountain, descended to the river, and continued along the beach for some distance.

"We entered an extensive valley or plain, known by the name of Standing Stone; made a halt here for about half an hour for refreshments," Hubley wrote. "This place derives its name from a large stone standing erect in the river immediately opposite this plain. It is near twenty feel in height, fourteen feet in width, and three feet in depth."

Hubley described the valley as being very grassy and exceedingly fine, with timber of white oak, black walnut, and pine timber.

The soldiers took refreshment at Standing Stone. The main army set up camp to protect the boats, which made it only to Standing Stone on this day, while the light corps continued the march along the valley.

At about 3 p.m., the light corps crossed Wesauking Creek. It sent (sic) up camp along the river about a mile past the mouth of Wesauking Creek.

At about 4 p.m., some of Hubley’s officers discovered a small Iroquois encampment which had been vacant for a few days. There was a canoe nearby, which the officers absconded with.

Hubley reported that a scouting party sent up to Sheshequin a few days prior returned and reported no discoveries.

Wesauking – Aug. 9, 1779

Given their situation of detachment from the main army and being "considerably advance" into enemy territory, the members of the light corps stood under arms from 3 a.m. until daylight. After daylight, the guards were dismissed, but soldiers were under orders to be ready at a moment’s notice in the event of attack from Iroquois warriors.

"Previous to their dismissal my light infantry was sent out to reconnoiter the vicinity of encampment," Hubley wrote.

He reported that the infantry returned at 7 a.m., having made no discoveries.

The boats arrived in sight of the light corps at about 9 a.m. The men of the light corps received orders to get ready to march.

The main army arrived at about 10 a.m. and all moved out.

Hubley reported that the army marched through a difficult swamp. It crossed a small stream (now known as Lanning Creek) at the north end of the swamp and ascended a hill.

It descended the hill at noon and entered a small valley.

At one point, Sullivan’s troops on the west side of the Susquehanna encountered an Andaste village called Oscalui along Sugar Creek in what is today known as North Towanda Township. As per their orders, the soldiers destroyed the village, which is regarded as the last Native American attempt at occupation in the Susquehanna Valley.

Local history buff Ed Stevens noted that there are two monuments in North Towanda related to Sullivan’s March. One is t the corner of Olde Mills and McEwen roads, near the site of Oscalui. The other is on private property off Crest Road, just north of Crystal Springs. According to Stevens, the plaque was removed from that monument when it was moved in 1952 and has not been replaced. He said the state Monuments Commission claims to be in possession of the plaque and has said it would replace it, but has not yet done so.

After the destruction of Oscalui, the army continued its march up the Susquehanna, ascending a high mountain known as Break Neck Hill.

"This mountain derives its name from the great height, of the difficult and narrow passage, not more than one foot wide, and remarkable precipice which is immediately perpendicular, and not less than 180 feet deep," Hubley wrote. "One misstep must inevitably carry you from top to bottom without the least hope or chance of recovery."

At (the) north end of the mountain, the army entered a mountainous and beautiful valley called Sheshecununk.

"Gen. Sullivan, with a number of officers, made a halt here at a most beautiful run of water, took a bite of dinner, and proceeded on along the valley, which very particularly struck my attention," Hubley wrote. "Any quantity of meadow may be made here; abounds with all kinds of wood, particularly white oak, hickory, and black walnut; the ground covered with grass and pea vines; the soil in general very rich."

At about 4 p.m., the army arrived on the bank of the river, where it encamped "on a most beautiful plain."

Hubley noted that the meadow had grass remarkably thick and high.

On the site, soldiers discovered fresh tracks of the Iroquois. They also discovered evidence of a recent fire and freshly-cut boughs.

It "appeared as if the place had just been occupied a few hours before

our arrival," Hubley wrote.

|

Sheshecununk – Aug. 10, 1779

Rain fell again on this day. The boats also did not arrive at Sheshecununk until 9 a.m. For those reasons, the army was ordered to remain at Sheshecununk until it received further orders. The men prepared two days provisions. "One regiment from each of the brigades attended Gen. Sullivan," Hubley wrote. He noted that the general and field officers of the army went on a reconnaissance mission along the Susquehanna River and the Tioga Branch, which was about three miles upstream from the camp. They returned at about 4 p.m., reporting no discoveries. |

Sheshecununk – Aug. 11, 1779

Following orders, the army moved out at 8 a.m. in its usual order. Hubley noted that the light corps moved out 30 minutes before the main army and took post on the banks of the river near the fording place.

"On the arrival of the main army and boats, Col. Forest drew up his boat at the fording place, and fixed several six-pounders on the opposite shore in order to scour the woods and thickets, and prevent any ambuscade from taking place," Hubley wrote.

The light corps marched by platoons. The soldiers linked themselves together, to combat the rapid current, and crossed the river at about 9 a.m.

"They immediately advanced about one hundred yards from the river, and formed in line of battle, in order to cover the landing of the main army, which was safely effected about 10 o’clock a.m.," Hubley wrote.

By 10:30, the army had moved out. The army marched through a dark, difficult swamp which was laden with weeds and considerable underwood. Hubley noted that the swamp was interspersed with large timber, chiefly buttonwood.

"We then entered the flats near the place on which Queen Esther’s palace stood, and was destroyed by Col. Hartley’s detachment last fall," Hubley wrote. "The grass is remarkably thick and high. We continued along the same for about one mile, and arrived at the entrance of Tioga Branch into Susquehanna about 1 o’clock."

The army crossed the Tioga Branch "and landed on a peninsula of land which extends towards Chemung, and is bounded on the east by Susquehanna, and on the west by Tioga Branch."

The army marched up the peninsula, known as Tioga Point, and camped there.

"This peninsula is composed of excellent meadow and upland grass is plenty, and timber of all kinds, and soil in general good."

After setting up camp, a scout of eight men was ordered on a reconnaissance mission to check out Chemung.

After seeing relatively little action in the first two weeks of the march, the army had little idea what action it would see in the next two weeks.

Editor’s Note: Part Three of this series will be published next Sunday.

Sullivan’s Army Sets Up Fort at Modern-day Athens

12 August 2001

About two weeks after leaving from Wyoming (modern-day Wilkes-Barre), Gen. John Sullivan’s army arrived at Tioga Point (modern-day Athens), where it would form a garrison for the protection of the western army.

Gen. George Washington ordered Sullivan and his men on a scorched-earth campaign up the Susquehanna Valley and into the Finger Lakes. At the same time, he ordered Gen. Daniel Broadhead to march an army up the Allegheny Valley to the west and Gen. James Clinton to march an army up the Hudson and Mohawk Valleys. They were ordered to destroy all villages of the Six Iroquois Nations they encountered in retaliation for raids on colonial settlements. They were also commanded to engage any Iroquois or British troops they encountered.

The long-term plan called for Clinton to lead his army from the Mohawk Valley, through the headwaters of the Susquehanna, to Tioga Point to join Sullivan’s army. Sullivan’s army would then combine with Broadhead’s army for an attack on the British stronghold at Fort Niagara.

Two weeks after leaving from Wyoming, Sullivan’s army had seen relatively little action. That would soon change.

The following account is derived from the journal of Lt. Col. Adam Hubley,

an officer in Sullivan’s light corps.

| Tioga Point – Aug. 12, 1779

In keeping with orders to cover Broadhead’s western army, a garrison was established at Tioga Point, 2 ½ miles from the confluence of the Tioga Branch (modern-day Chemung River) and the Susquehanna River. At that point on the peninsula, the two rivers are only 190 yards apart, Hubley noted. He wrote that sundry works were built extending from river to river for the security of the garrison. A scout sent out the previous evening returned from Chemung at about 11 a.m., having made several discoveries. With information gained from the scouting mission, a council of war sat. The council determined that soldiers should make the 12-mile trek to Chemung with the purpose of destroying the Iroquois settlement there. Two regiments were left at the garrison. The remainder of the soldiers were ordered to be ready for an immediate march. The army left for Chemung at about 8 p.m. |

Chemung – Aug. 13

"Light corps, under command of Gen (Edward) Hand led the van, then followed Gens. (Enoch) Poor and (William) Maxwell’s brigades, which formed main body, and corps de reserve, the whole under the immediate command of Maj. Gen. Sullivan," Hubley wrote. "The night being excessively dark, and the want of proper guides, impeded our march, besides which we had several considerable defiles to march through, that we could not possibly reach Chemung till after daylight."

Hubley noted that the morning was particularly foggy, which gave the army an advantage, in that it would not easily be spotted by the Iroquois. However, it also hampered colonial efforts, in that soldiers could not find the town.

"We discovered a few huts, which we surrounded, but found them vacated," Hubley wrote. "After about one hour’s march we came upon the main town."

Once the main town was discovered, the army devised a plan to take the inhabitants by surprise.

"Two regiments, one from the corps, and one from main body, were ordered

to cross the river and prevent the enemy from making their escape that

way, should they still hold the town," Hubley wrote. "The remainder of

the light corps, viz., two independent companies and my regiment, under

command of Hand, were to make the attack on the town. Gen. Poor was immediately

to move up and support the light corps."

| Hubley noted that the scouting party of the previous day had probably

been discovered, as the soldiers moved in to find an empty village. The

inhabitants had carried off all of their furniture and livestock.

The army easily took the village at 5 a.m. "The situation of this village was beautiful," Hubley wrote. "It contained fifty or sixty houses, built of logs and frames, and situate on the banks of Tioga Branch, and on a most fertile, beautiful, and extensive plain, the lands chiefly calculated for meadows, and the soil rich." |

|

At Newtown, infantrymen discovered fires burning, a sleeping dog, a number of deer skins, and some blankets. They were ordered to continue up the path, scouting out the area.

The infantrymen continued on for about a mile when they encountered some action.

"The first fires were discovered, when our van was fired upon by a party of savages, who lay concealed on a high hill immediately upon our right, and which Capt. Bush (who commander the right flank) had not yet made," Hubley wrote. "We immediately formed a front with my regiment, pushed up the hill with a degree of intrepidity seldom to be met with, and, under a very severe fire from the savages, Capt. Bush, in the meantime, endeavored to gain the enemy’s rear. They, seeing the determined resolution of our troops, retreated and, according to custom, previous to our dislodging them, carried off their wounded and dead, by which means they deprived us from coming to the knowledge of their wounded and dead."

Hubley noted that the ground on the opposite side of the ridge was very swampy, favoring the Iroquois retreat.

The colonial army lost six men in the skirmish. Another 12 were wounded. Of the 18 casualties, 16 (were) from Hubley’s regiment.

"After gaining the summit of the hill, and dislodging the enemy, we marched by the right of companies in eight columns, and continued along the same until the arrival of Gen. Sullivan," Hubley wrote. "We then halted for some little time, and then returned to the village, which was instantly laid in ashes, and a party detached to cross the river to destroy the corn, beans, &c., of which there were several very extensive fields, and those articles in the greatest perfection."

The natives were not happy about losing their village and their food source to the army. As the brigades of Poor and Maxwell were burning the extensive crops on the south side of the Tioga Branch, the warriors fired on them. One soldier was killed and several more were wounded.

After the mission was completed, the army returned to the destroyed village for a short time, then returned to Tioga Point. The army carried the dead soldiers back to Tioga Point for interment.

When the army arrived at Tioga Point at 8 p.m., Hubley noted that the soldiers were considerably fatigued.

"The expedition from the first to last continued 24 hours, of which time my regiment was employed, without the least intermission, twenty-three hours," Hubley wrote. "The whole of our march not less than 40 miles."

Tioga Point – Aug. 14

At 10 a.m., the soldiers at Tioga Point held funeral services for their dead comrades, who were interred with military honors, with the exception of the firing of weapons.

"Parson Rogers delivered a small discourse on the occasion," Hubley wrote.

There was not much of note that happened on this day. Hubley spent most of the day writing to his friends in Lancaster and Philadelphia. Those letters were forwarded that evening.

Tioga Point – Aug. 15

Seven hundred men were ordered to march on the grand parade for inspection.

They were furnished with ammunition and eight days’ provision in preparation for a march up the Susquehanna to meet with Clinton’s army.

At about 2 p.m., a firing was heard immediately opposite the army’s encampment, on the west side of the Tioga Branch.

"A number of Indians, under cover of a high mountain, advanced on a large meadow or flat of ground, on which our cattle and horses were grazing. Unfortunately, two men were there to fetch some horses, one of which was killed and scalped, the other slightly wounded, but go clear. One bullock was likewise killed, and several public horses taken off."

Hubley’s regiment was ordered to pursue the warriors. The regiment ascended the mountain and marched two miles along the summit, but the enemy was long-gone. Hubley’s men scoured the mountains and valleys in the area, but found nothing. They returned to camp, much fatigued, at about 5 p.m.

Tioga Point – Aug. 16

At about 1 a.m., several of the Continentals alarmed the camp by firing their guns. The light corps stood under arms while several patrols were sent to scout out the front of the encampment. The patrols returned at daybreak, having made no discoveries.

At about 1 p.m., the 700-man detachment under Gen. Poor’s command, marched up the Susquehanna to meet with Clinton’s army. Hand was ordered to go with Poor’s detachment, leaving command of the light corps with Hubley.

Tioga Point – Aug. 17

Much of the day was quiet. The excitement didn’t start until evening.

At about 7 p.m., a firing was heard about five hundred yards from the light corps’ encampment. Hubley sent out 50 men to find out who was shooting out there.

The men returned at about 8 p.m., and reported that 11 warriors had waylaid a few pack horsemen, who were returning with their horses from pasture.

"They had killed and scalped one man, and wounded another," Hubley wrote. "The wounded man got safe to camp, and the corpse of the other was likewise brought in."

Another alarm was fired by a Continental at about 11 p.m. That alarm proved false, Hubley wrote.

Tioga Point – Aug. 18

Having had enough of the Iroquois warriors sneaking around the encampment and picking off soldiers as they tended to the animals, the army devised a plan to entrap the warriors.

An officer and 20 men were each sent out to the mountain opposite the encampment, an island above the encampment on the Tioga Branch and the woods a mile and a half in front of the light corps encampment. They had orders to waylay and "take every other means to take" the warriors. Each group was to be relieved daily by another officer and 20 more men until the army left the ground.

At the request of several of the men, Dr. Rogers delivered a discourse in the Masonic form on the deaths of Capt. Davis of Pennsylvania’s 11th and Lt. Jones of the Delaware regiments. On April 23, 1778, the two were marching with a detachment for the relief of the garrison at Wyoming when they were "most cruelly and inhumanly massacred and scalped by the savages, emissaries employed by the British king."

Both were members of the honorable and ancient Society of Freemen, Hubley noted.

"A number of brethren attended on this occasion in proper form, and the whole was conduced with propriety and harmony," Hubley wrote. "Text preached on this solemn occasion was the first clause in the 7th verse of the 7th chapter of Job, ‘Remember my life is but wind.’ "

Editor’s Note: Part four of this series will be published next Sunday.

Poor Returns with Clinton, Army Prepares for March to the Finger Lakes

19 August 2001

On this week, 222 years ago, Gen. John Sullivan’s army had just experienced the first real combat – and casualties – of its scorched-earth campaign against the Six Iroquois Nations.

It lost seven men in the Aug. 13 Chemung Ambush. In the following days, warriors lurking around the perimeter of the army’s Tioga Point (modern-day Athens) encampment killed two more men. Several more men were wounded in the skirmishes.

Soldiers continued to shore up the encampment, establishing a garrison at Tioga Point, with the intent of covering the western army, led by Gen. Daniel Broadhead. As an added measure of protection, an officer and 20 men were positioned in three key locations around the encampment. They were relieved daily.

During the previous week, Gen. Enoch Poor led 70 men up the Susquehanna River to meet Gen. James Clinton’s army.

Clinton’s army was on a similar search-and-destroy mission. It had marched up the Hudson and Mohawk valleys, then through the headwaters of the Susquehanna River. In the area of modern-day Cooperstown, N.Y., destroying Iroquois villages along the way and doing battle with any Iroquois or British troops it encountered.

Poor was ordered to meet up with Clinton and his men and bring them back to the garrison at Tioga Point. He was expected to return with Clinton’s army within the next few days.

The following account is derived from the journal of Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, an officer in Sullivan’s light corps.

Tioga Point – Aug 19

The men Sullivan positioned around the encampment seemed to be accomplishing their task. There were no attacks from Iroquois warriors reported.

Hubley had only four words to describe the activities of the day.

"Nothing remarkable this day," Hubley wrote.

The army continued to work around the fort in preparation for the coming arrival of Poor and Clinton and the ensuing march to the Six Nations’ stronghold in the Finger Lakes.

Tioga Point – Aug 20

Hubley reported that it rained for most of the day, sometimes heavily.

Lt. Boyd arrived at the encampment with accounts of Clinton’s movements along the Susquehanna. He said Poor and Clinton had formed a junction at Chokoanut, about 35 miles upstream from the encampment, and should be expected to return to camp in the next day.

Tioga Point – Aug 21

The heavy rain of the previous day had an adverse effect on the army’s plans.

"The detachments under Gens. Clinton and Poor, on account of the very heavy rain yesterday, did not reach this encampment as was expected," Hubley noted.

Tioga Point – Aug 22

It was a day of celebration for the colonial army.

Only a day behind schedule, Clinton and Poor’s detachments, with about 220 boats, arrived shortly after 10 a.m.

As Poor and Clinton passed the light corps encampment, they were saluted with 13 rounds, Hubley noted. They were also greeted by fife and drum music.

The men guarding the perimeter seemed to be working for the encampment. Iroquois attacks on soldiers had not been reported since the Aug. 17 incident at the horse pasture.

Tioga Point – Aug 23

The army suffered a blow on this day when an officer died and another wounded, though not at the hands of the Iroquois.

"By an accident of a gun, which went off, the ball of which entered a tent in which was Capt. Kimball, of Gen. Poor’s brigade, and a lieutenant," Hubley wrote. "The captain was unfortunately killed, and the lieutenant wounded."

With Clinton’s army now in the fold, there were alterations in several of the brigades. Col. Courtland’s regiment, once under Hubley’s command, was annexed to Clinton’s brigade. Col. Older’s regiment was split between Poor’s brigade and Col. Butler’s regiment, and Maj. Parr’s corps were (sic) added to Gen. Edward Hand’s brigade.

The army now had its order set for the coming march into the heart of Iroquois territory.

Tioga Point – Aug 24

Men worked day and night making bags in which to carry flour.

At 5 p.m., the signal was sounded for the whole army to strike tents. The army marched a short distance in order to form the line of march.

Another gun was fired at 7 p.m., signaling the soldiers to encamp in proper order and be ready for an immediate march.

Hubley noted that Butler’s regiment was added to the light corps presumably replacing Courtland’s regiment.

Col. Shrieve took command of the garrison, known as Fort Sullivan, on this day, as Gen. Sullivan would be marching with the army.

Supplies were moved on this day to the garrison, Hubley noted.

Tioga Point – Aug 25

"This morning was entirely devoted to packing up and getting every thing in readiness for an immediate march," Hubley wrote.

While the army had planned on marching on this day, it was not to be. A heavy rain started falling at about 11 a.m. and continued through the greater part of the day.

The precipitation was enough that it prevented the army from moving out. The sacking of Iroquois villages would have to wait another day.

Editor’s Note: Part five of this series will be published next Sunday.

Sullivan’s Army Prepares for Journey Into the Heart of Iroquois Country

26 August 2001

It had been nearly a month since Gen. John Sullivan led his army from Wyoming, near modern-day Wilkes-Barre on a search-and-destroy mission into Iroquois country.

The army had arrived at Tioga Point (modern-day Athens) and established Fort Sullivan, a base of operations from which to continue its mission into the heart of the Six Nations, the Finger Lakes region of modern-day New York state.

Gen. Enoch Poor had led a brigade up the Susquehanna River, meeting up with Gen. James Clinton’s brigade at Chokoanut (in modern-day Susquehanna County). Clinton had been on a similar mission and arrived at Chokoanut from the Mohawk Valley, via the headwaters of the Susquehanna. The brigades then returned to Fort Sullivan.

During the past week, 222 years ago, the army was laying low at Fort Sullivan, preparing for the trek into the Finger Lakes and defending against sniping by Iroquois warriors in the areas surrounding the fort.

The following account is derived from the journal of Lt. Col. Adam Hubley, an officer in Sullivan’s light corps.

Tioga Point – Aug. 26, 1779

Despite being ordered to be ready to march at 8 a.m., the army was not perfectly ready to go at that time.

The army was signaled to march at 11 a.m.

"The whole took up the line of march in the following order, namely: Light corps, commanded by Gen. Edward Hand, marched in six columns, the right commanded by Col. Zebulon Butler, and the left by myself," Hubley wrote. "Major Parr, with the riflemen, dispersed considerably in front of the whole, with orders to reconnoiter all mountains, defiles, and other suspicious places, previous to the arrival of the army, to prevent any surprise ambuscade from taking place. The pioneers, under command of a captain, subaltern, then followed after, which preceded the park of artillery; then came on the main army, in two columns, in the center of which moved the pack horses and cattle, the whole flanked on right and left by the flanking divisions, commanded by Col. Dubois and Col. Ogden, and rear brought up by Gen. James Clinton’s brigade."

The army marched about three miles to the upper end of Tioga flats, where it camped out.

Hubley noted that he gave of one of his horses to Capt. Bond due to his indisposition. Bond was then given leave to either continue at Fort Sullivan or go to Wyoming until the return of his regiment from the expedition.

Tioga Flats – Aug. 27

Delays struck the army again today. The army did not march until 8:30 a.m.

Prior to the march, the pioneers, under cover of the rifle corps, advanced to the first and second narrows several miles ahead of the army’s encampment. They were employed in mending and cutting a road for the pack to pass.

"The army marched in same order of yesterday, the country through which they had to pass being exceedingly mountainous and rough, and the slow movements of the pack considerably impeded the march," Hubley wrote.

The army marched about six miles, arriving at the narrows at the lower end of Chemung at about 7 p.m.

The light corps encamped near the entrance of the narrows, in front of some extensive cornfields. Some refugee Tories who defected to the main army camped a mile to the rear of the light corps.

"After encamping had an agreeable repast of corn, potatoes, beans, cucumbers, watermelons, squashes, and other vegetables, which were in great plenty, (produced) from the cornfields already mentioned, and in the greatest perfection," Hubley wrote.

A scouting party was sent up to Newtown on a reconnaissance mission.

Chemung – Aug. 28

Because the aforementioned narrows prohibited the passage of the artillery, pack horses and cattle, Hubley spent the early part of the day searching for a fording place at which they could cross, enabling the army to take Chemung.

Once a fording place was found, the army moved.

"The rifle corps, with Gen. (William) Maxwell’s brigade, and left flanking division of the army, covering the park, pack horses, and cattle, crossed to the west side of the river, and about one and a half mile above recrossed the same, and formed a junction on the lower end of Chemung flats with the light corps," Hubley wrote. "Gens. (Enoch) Poor and Clinton’s brigades, and right flanking division of the army, who took their route across an almost inaccessible mountain on the east side of the river, the bottom of which forms the narrows already mentioned."

Hubley noted that, with some difficulty, the summit was gained by the army.

"On the top of the mountain the lands, which are level and extensive, are exceedingly rich with large timber, chiefly oak, interspersed with underwood and excellent grass," Hubley wrote. "The prospect from this mountain is most beautiful; we had a view of the country of at least twenty miles round; the fine, extensive plains, interspersed with streams of water, made the prospect pleasing and elegant from this mountain. We observed, at some considerable distance, a number of clouds of smoke arising, where we concluded the enemy to be encamped."

A small party was sent across the Tioga Branch (Chemung River) to destroy some Iroquois huts. Those men were fired upon by warriors, who retreated almost immediately. The huts were destroyed and the soldiers returned unharmed.

The scouts sent out the previous evening returned, reporting the discovery of a great number of fires, Hubley noted.

From the extensive piece of ground covered by the fires, the scouts believed the enemy to be very formidable, and with intent to do battle. They also discovered four or five small scouting parties on their way toward the army encampment, possibly to reconnoiter the Continental Army.

"Since our arrival here a great quantity of furniture was found by our

soldiers which was concealed in the adjacent woods," Hubley noted.

| The army arrived at the upper part of Chemung town at about 6 p.m.,

having marched only two miles on a straight course. It encamped there.

"From the great quantities of corn and other vegetables here and in the neighbourhood, it is supposed (the Iroquois) intended to establish their principal magazine at this place, which seems to be their chief rendezvous, whenever they intend to go to war; it is the key to the Pennsylvania and New York frontier," Hubley wrote. "The corn already destroyed by our army is not less than 5,000 bushels upon a moderate calculation, and the quantity yet in the ground in this neighbourhood is at least the same, besides which there are vast quantities of beans, potatoes, squashes, pumpkins, &c., which shared the fate of the corn." |

|

Upper Chemung – Aug. 29

The discovery of Iroquois presence near Newton Undoubtedly made the continental soldiers anxious. Certainly, the soldiers were on their guard this morning.

The army moved out with great trepidation at about 9 a.m.

"The riflemen were well-scattered in front of the light corps, who moved with the greatest precision and caution," Hubley wrote. "On our arrival near the ridge on which the action of the 13th (Chemung ambush) commenced with light corps, our van discovered several Indians in front, one of whom gave them a fire, and then fled. We continued our march for about one mile; the rifle corps entered a low, marshy ground which seemed well-calculated for forming ambuscades."

Still cautious, the army advanced. Several more Iroquois warriors were discovered. The warriors fired on the army, then fled, Hubley noted.

"Major Parr, from those circumstances, judged it rather dangerous to proceed any further without taking every caution to reconnoiter almost every foot of ground, and ordered one of his men to mount a tree and see if he could make any discoveries," Hubley wrote.

The soldier made a discovery on the land that is today Exit 58 of New

York state Route 17 in Lowman, N.Y.

|

"After being some time on the tree, he discovered the movements of

several Indians, which were rendered conspicuous by the quantity of paint

they had on them, as they were laying behind an extensive breastwork, which

extended at least half a mile, and most artfully covered with green boughs,

and trees, having their right flank secured by the river, and their left

by a mountain," Hubley wrote. "It was situated on a rising ground – about

one hundred yards in front of a difficult stream of water, bounded by the

marshy ground already mentioned on our side, and on the other, between

it and the breast works, by an open and clear field."

Parr informed Hand of his discoveries. Hand immediately advanced the light corps to within three hundred yards of warriors, and prepared for battle. |

| "The rifle corps, under cover, advanced, and lay under the bank of

the creek within one hundred yards of the lines," Hubley wrote.

Sullivan arrived with the main army. He ordered the rifle and light corps to remain in their positions. The left flanking division, under command of Ogden, was ordered to take post on the left flank of the light corps. Maxwell’s brigade was ordered to the rear as a reserve corps. Col. Proctor’s artillery was ordered to the front and center of the light corps, immediately opposite the breastwork. "A heavy fire ensued between the rifle corps and the enemy but little damage was done on either side," Hubley wrote. |

|

Poor and Clinton were ordered to lead their brigades to the right flank, with the intent of taking the enemy’s flank and rear.

Proctor was ordered to have his artillery prepared to attack the lines, first allowing sufficient time for Poor and Clinton to gain their intended stations.

At about 3 p.m., the battle began.

"The artillery began their attack on the enemy’s works," Hubley wrote. "The rifle and light corps in the meantime prepared to advance and charge; but the enemy, finding their situation rather precarious, and our troops determined, left and retreated from their works with the greatest precipitation, leaving behind them a number of blankets, gun covers, and kettles, with corn boiling over the fire."

Poor and Clinton could not reach their intended stations in the prescribed time, Hubley wrote. He noted that the warriors had known of the approaching brigades and posted troops on top of a mountain over which Poor and Clinton would need to advance.

"On their arrival near the summit of (the mountain), the enemy gave them a fire, and wounded several officers and soldiers," Hubley wrote. "Gen. Poor pushed on and gave them a fire as they retreated, and killed five of the savages."

Three Continental soldiers and twelve enemy soldiers died in the battle. Of the 12 enemy soldiers, nine were Iroquois. Two Iroquois warriors were taken prisoner.

After debriefing the prisoners, the army determined that the enemy was 700 men strong. Five hundred of the men were Iroquois warriors, chiefly of the Seneca, Cayuga and Mohawk nations. Two hundred were Tories, with about 20 British troops. They were commanded by Col. John and his son, Capt. Walter Butler, Mohawk Capt. Joseph Brant and Capt. John McDonnell, Hubley wrote.

"The prisoners further informed us that the whole of their party had subsisted on corn only for this fortnight past, and that they had no other provisions with them," Hubley wrote. "And that their next place of rendezvous would be at Catherine’s town, and Indian village about twenty-five miles from this place (near modern-day Montour Falls, N.Y.)."

"The infantry pushed on towards Newtown," Hubley wrote. "The main army halted and encamped near the place of action, near which were several extensive fields of corn and other vegetables."

The infantry returned at about 6 p.m. and encamped near the main army.

|

Near Newtown – Aug. 30

Sullivan decided to delay movement for a day so the dead could be buried and the sick and injured could be sent back to Fort Sullivan. The army set about destroying the great quantities of corn, beans, potatoes, turnips, and other vegetables in the area early in the day. It also destroyed the village of Newtown. Later, rain set in, which prompted the army to remain encamped. |

The troops were also employed in gathering provisions for eight days. Hubley noted that the reason of drawing this great quantity at one time was consideration of the extensive campaign ahead, and the time of consequence it will require to complete it.

Due to the want of pack horses for transporting the provisions, the army was forced to have some soldiers carry provisions.

Hubley noted that those responsible for supplying the western army with everything necessary to carry through the expedition had not followed through. For that reason, Sullivan was forced to address the troops.

Sullivan said the commander-in-chief, George Washington, had used every effort to obtain supplies to the army, but was unable to do so. He said Washington feared that current supplies would not last.

For that reason, Washington requested that flour, meat and salt be rationed.

Sullivan said that Washington "flatters himself" that the brave troops would "readily consent" to the rations to accomplish the goals of the exhibition (stet).

He noted that the Iroquois has subsisted for two weeks on nothing but corn and said troops "who so far surpass them in bravery and true valour" would not "be outdone in that fortitude and perseverance."

Sullivan said the rations would be in place in areas where the vegetables were plentiful and could take the place of a part of the common ration.

That evening, the officers passed on the message to the soldiers who agreed "without a dissenting voice."

"This remarkable instance of fortitude and virtue cannot but endear those brave troops to all ranks of people, more particularly as it was so generally and cheerfully entered into without a single dissenting voice," Hubley wrote.

Near Newtown – Aug. 31

The army moved out at about 9 a.m.

It marched about 4-1/2 miles "through a broken and mountainous country, and an almost continuous" narrows to the east of the Cayuga Branch (Newtown Creek).

To the west of the creek "for that distance was an excellent plain, on which large quantities of corn, beans, potatoes, and other vegetables stood and were destroyed by us the preceding day."

The army continued up the Cayuga Branch and crossed at the fork "with a stream of water running east to west."

At that point, the army came upon and destroyed the small Iroquois village of Kanawaholla (modern-day Elmira, N.Y.). Hubley noted that the soldiers found great quantities of furniture, some of which was carried off. The rest was destroyed.

Meanwhile, Col. Dayton’s men chased some fleeing warriors up the Tioga Branch to the village of Runonvea, which it promptly destroyed.

Following the sacking of Kanawaholla, at about 2 p.m., the main army continued up the path to Catherine’s town, an Iroquois village near the south end of Seneca Lake.

"About 5 o’clock, p.m., we encamped on a most beautiful plain, interspersed with marshes, well-calculated for meadows," Hubley wrote. "Wood – chiefly pine – interspersed with hazel brushes, and great quantities of grass.

Near Kanawaholla – Sept. 1

The light corps moved out at 9 a.m., meeting up with the main army, which had encamped near modern-day Horseheads, N.Y.

By 11 a.m., it had encountered a six-mile-long swamp. The path through it was almost impassible, Hubley wrote, due to the number of narrows, mountains and ravines and the thick underwood.

"The infantry, with the greatest difficulty, got through about half past nine o’clock, p.m.," Hubley wrote. "The remainder of the army, with the pack horses, cattle, & co., were chiefly the whole night employed in getting through."

As the infantry approached Catherine’s town, the soldiers were alarmed by a lot of noise, including the howling of dogs.

"A few of the riflemen were dispatched in order to reconnoiter the place," Hubley wrote. "In the meantime, we formed in two solid columns, at fixed bayonets, with positive orders not a man to fire his gun, but to rush on in case the enemy should make a stand. But the riflemen, who had been sent to reconnoiter the town, returned with the intelligence the enemy had left it."

The army then marched up the narrow road through the first part of the town, after which it crossed Catherine Creek and camped in some houses in a field immediately opposite.

"On our arrival, we found a number of fires burning, which appeared

as if they had gone off precipitately," Hubley wrote.

|

|

|

| Schuyler County Rte 414 | Schulyer County Rte 414 | Seneca County Rte 89 |

|

Finger Lakes – Autumn 1779

In the coming weeks, Sullivan’s army set about decimating the Iroquois villages in the region, including the Seneca capital at Jenesee (modern-day Geneseo, N.Y.). Not everything went according to plan. There were only a few major battles along the way, such as the Groveland Ambuscade in the western Finger Lakes. Broadhead’s army, marching up the Allegheny Valley from Fort Pitt, only made it to Salamanca. It never met up with Sullivan’s army for the planned attack on the British stronghold at Fort Niagara. Still, Sullivan’s expedition proved successful in exacting vengeance on the Six Nations for their raids on colonial settlements. It also effectively took the Iroquois out of the war; the warriors of the Six Nations were not a significant factor after 1779. |

The expedition did wonders for the Continental Army’s morale, which had been low. After the expedition, the colonists knew they had a chance to win the war. Before it, colonists worried about their safety in their own homes.

At the victorious army marched back to Fort Sullivan, it stopped at the south end of Catherine Creek long enough for Sullivan to sacrifice a number of worn-out horses.

Several years later, after the village of Fairport had been built at the site, village leaders paid homage to that occurrence. They renamed their village "Horseheads."

Just a few miles up Newtown Creek stands Sullivanville, N.Y., named in honor of the conquering general.

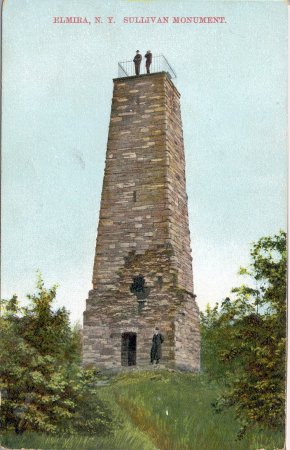

These are but two of the local reminders of this expedition, which proved

so important in turning the tide of the Revolutionary War. There are monuments

along Twin Tiers highways, back roads, municipal streets – even a private

back yard in North Towanda – denoting important events which occurred during

Sullivan’s Campaign, which proved so important in enabling the colonies

to win the Revolutionary War, setting the stage for the creation of the

United States of America.

|

Near Newtown – August 30, 1779 "The commander-in-chief informs the troops that he used every effort to procure proper supplies for the army, and to obtain a sufficient number of horses to transport them, but owing to the inattention of those whose business it was to make tile necessary provision, he failed of obtaining such an ample supply as he wished, and greatly fears that the supplies on hand will not, without the greatest prudence, enable him to complete the business of the expedition. "He therefore requests the several brigadiers and officers commanding corps to take the mind of the troops under their respective commands, whether they will, whilst in this country, which abounds with corn and vegetables of every kind, be content to draw one half of flour, one half of meat and salt a day. And he desires the troops to five their opinions, with freedom and as soon as possible. "Should they generally fall in with the proposal, he promises they shall be paid that part of the rations which is held back at the full value in money. "He flatters himself that the troops who have discovered so much bravery and firmness will readily consent to fall in with a measure so essentially necessary to accomplish the important purpose of the expedition, to enable them to add to the laurels they have already gained. |

| Earliest Sullivan's Monument at Newtown Battlefield |

"The enemy have subsisted for a number of days on corn only, without either salt, meat, or flour, and the general cannot persuade himself that troops, who so far surpass them in bravery and true valour, will suffer themselves to be outdone in that fortitude and perseverance, which not only distinguishes but dignifies the soldier. He does not mean to continue this through the campaign, but only wishes it to be adopted in those places where vegetables may supply the place of a part of the common ration of meat and flour, which will be much better than without any.

"The troops will please to consider the matter, and give their opinion as soon as possible."

| The History Center on Main Street, 83 N. Main Street, Mansfield PA 16933 histcent83@gmail.com |