|

| The History Center on Main Street, 83 N. Main Street, Mansfield PA 16933 histcent83@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|

By Kathy Myron in Daily Review (Staff Writer) 1987

Laquin—by Charles Albert Consil (First baby born at Laquin, Pa., Sept.3, 1903)

I stand with my head bowed

And gaze into the past

Everything’s changed now,

I knew it wouldn’t last

I hear echoes of laughter

Voices bright and gay

I see houses and people

In memory of yesterday

I hear the mill whistle blowing

The band saws whine and din

I see Mother’s face before me

I’m home again at Laquin

All life has its beginning

It has its sorrowing and pain

Let’s trust in the hereafter

That we all find joy again

That God is good and His Promises

Will surely come true some day

That we’ll meet in Laquin Together

This time we’ll come to stay

|

A patchwork quilt of memories was shared by those who gathered at Laquin

to reminisce about beloved days past. This year’s reunion took place on

the traditional third Sunday in July. They came to Hugo’s Grove to eat,

talk, listen and remember, relaxing under a pavilion within the foundations

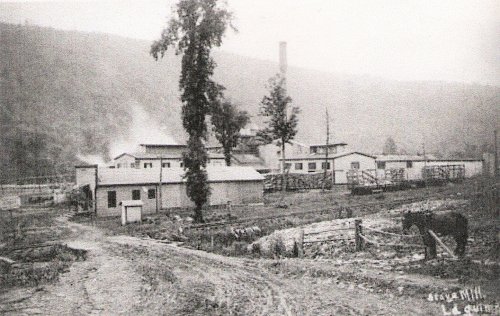

of the old stave mill.

Among the thinning ranks who grew up or worked in the old boomtown was Lola Bailey Long. (Lola Bailey Long lived in Powell, Pa) Mrs. Long was twenty-two years old in 1923 when she taught music to eighth graders at the Laquin School She recalled of her class of 30: "They didn’t realize what ‘music’ was-just hard work." |

Across from the school, she related, was the area known as "The Jungles," where recent Italian immigrants made their home. There the houses were almost on top of one another. A rag-tag lot of children, according to Mrs. Long, but well-behaved. When an occasional student needed it, Mrs. Long would "give them a good dressing-down, loud enough so they’d remember it."

The former music teacher defended the families’ roughness, explaining: "Every family was busy. They were hard workers—the average yard worker got paid just 50 – 75 cents a day."

She said that the workers charged what they bought at the company store, and then owed most of their pay at the end of the week.

Mrs. Long shivered as she shared her memories of a dark-complexioned

Polish man known as Black Alex. "His wife died, he lived with his son,

but he enjoyed his beer," she told with good humor. "he worked sometimes,

drank the rest of the time, and one day came to the school to kill the

principal, Bob Beech. It got pretty noisy. Some workemen heard the rumpus

and came to help. I was afraid. After that he moved to Powell. Powell quieted

him down, he never caused any more trouble.

| Mrs. Long left her family’s farm in Powell every school day to ride

the train to Laquin. Wide-eyed she recalled one different and exciting

ride home. Mr. Jim Coleman, roadmaster on the S & NY took Helen Carrol

(another school teacher) and I from Laquin to Powell on the hand cart.

Well, I tell you, I thought every curve, I'’ land in the Schrader Creek!

He was really traveling. That was a fast ride—the last one I ever took."

Mrs. Long remembered more ordinary days commuting: Train crews got water from the Schrader Creek at the Lamoka stop where another teacher, Mary Hartman, boarded. "The coach wasn’t clean. You’d have to be careful if you wore a dress. Matt Manix was the conductor. He was jolly, full of fun—he wasn’t very busy taking tickets." |

|

Recalling her family’s home, Mrs. Eddy described: "There was an old cooking range in the kitchen and heating stove for the living room. That’s all anybody had. Sometimes snow blew in through cracks in the bedroom windows."

"We lived below quite a long stretch of land down on the plain. The shoemaker’s house and another neighbor’s house were there. Children would run and play."

Mrs. Eddy said that while Laquin men worked hard in the mills, the women were kept busy with their own work at home. "Mother was a great worker, always cooking and cleaning for four children." Recalling meals of meat, potatoes, vegetables and homemade bread, she noted "there wasn’t much of a variety, the meat was mainly pork or fish."

She explained that hucksters came in from Sullivan County once a week

with vegetables to sell. "Four or five different ones would come to your

door to see if you wanted to buy anything. Two horses pulled a lumber wagon

full of vegetables; potatoes..apples, whatever was in season."

|

As a girl, Mrs. Eddy worked and babysat for the Ed Counsil family.

She said their baby, Charles was the first child born in Laquin, On Sept.

2, 1903. "Ed Counsil was manager of the Laquin store. He ran the whole

thing. You could buy anything from a pound of butter to a suit of clothes.

They had ‘everything’. It was a big company store.

Becoming the bride of Alex Eddy while living in Laquin, Daisy was dazzled

with the square dances they attended. She was proud of her husband who

was a caller. "I was young and hadn’t been anywhere so we’d go to dances.

He’d call ‘alamand left’ and so on; I never could remember the calls, but

he could.

|

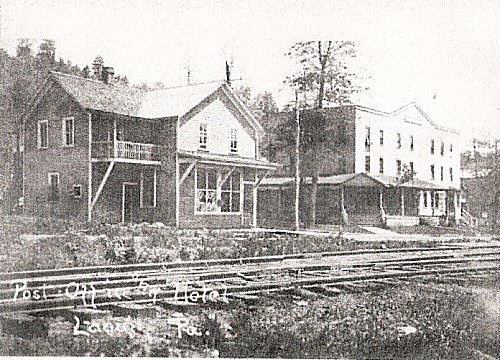

"People were happy", Mrs. Eddy remembers, "they didn’t have much time off from work. They enjoyed themselves at the dances. They were held upstairs over the pool hall and ice cream restaurant." Daisy explained that only ice cream and soft drinks were served in the restaurant. "You went to the hotel if you wanted food." She noted.

Mrs. Eddy tells how trips to the movie theatre in Towanda were a rare treat in those days. "You didn’t see pictures in your home then. You had to go down to the Keystone. You could come down in the evening. You had to stay all night and catch the morning train." Later, Alex Eddy bought an "old Maxwell car". They were then able to drive to Towanda and return the same evening.

As a young couple, the Eddy’s bought a five-room house "below the lumber yard" for $50. Later they moved to a six-room house which they rented for $5.

Although there wasn’t much leisure time to be had, the men of Laquin

managed to find time for fishing, hunting, pool playing and baseball. The

women were most often tied to their homes, busy with children and housework,

Mrs. Eddy related.

|

"My husband played baseball on the first Laquin team," Mrs. Eddy said proudly. "And he loved to hunt. He killed a lot of foxes. He killed a big bear up on the mountain from Laquin. People came begging to taste the bear meat. It was very good. Like beef. Alex had a couple of bear dogs. A bear dog’ll chase a bear if it finds it in the woods. "I had chickens, great laying chickens. They were kind of tan with silvery feathers around their necks. They could run right out in the woods. My father-in-law, I called him ‘Gramps’ (Orrlando "Bob" Eddy) finally sold the flock. |

|

The Eddy’s would have three sons while living at Laquin: Lloyd, Glen and Rex. Mrs. Eddy explained that her youngest son, Rex, was born at home during a blizzard. She can laugh about it now: "The coldest winter they had in 62 years and that baby had to be born in that deep snow! Dr. Bevens (of Leroy) came over the mountain on the back of a mule. The snow fell 48 inches deep the night he was born. That was March 23, 1916. The Doctor couldn’t get back home that night."

The Eddy boys went fishing in a pond at Laquin and caught "Long strings of fish." The Schrader Creek was badly polluted though, Mrs. Eddy said. "The water looked black. They put that chemical in where the creek was low. The stones were black. My kids would sneak down and wade in and then yell back to show me they got across, but they didn’t hang around long. It was smelly, too."

Mrs. Eddy’s clear blue eyes were pensive as she spoke about the demise of Laquin. Her family, forced to move, went to Monroeton in 1920.

"They cut all the timber, the job was done. They wanted everybody out of the way I figure. The company owned the houses. They probably ordered everybody out so they could tear the houses down and sell the lumber. They didn’t want no buildings left. They tore up the railroad tracks and everything."

Daisy Eddy won’t sit still for a picture—"I always did run from a camera"—but you can glimpse something of her heart and soul in these few wistfully spoken words:

"I missed the whistle blowing after we moved away…I missed that old whistle sounding out to the mill."

She recalls being paid $100 a month for her teaching services: "That was a lot of money." She admitted having fun spending it.

"I was a hat woman. Ask Clayton Maryott! I’d pay $15 for a hat. When you went shopping in Towanda you put your very best dress and shoes and hat on, and oftentimes gloves."

Evans and Chaffee ("At first it was Evans and Rooker") and Bullard’s Racket Store ("You could find anything there") and J. C. Swingles were among stores she patronized.

Laquin was famous for its western beef, she said. "I bought meat in Laquin to take home. Irwin Wilcox was the butcher. We did have fresh vegetables; I remember celery.

"Harry Bull ran the hotel. My parents were so fond of blood-orange soda.

The men used to take beer from the hotel in a tin pail with a cover on

it."

|

Also adding her memories was Florence Dale Covey Henry, who said that

it was good just to ride up the road to Laquin to remember where her family

once lived. "My father (James Dale) got his fingers caught in the air hammer

in the old saw mill. Dr. Coon took him to Towanda for help. It was a long

ride by horse and buggy. They stitched one finger back on, two fingers

were lost."

Her son, Rev. Arnold Covey of Athens, talked about Laquin’s "hot" baseball team—"Herb Henry, Clyde Dale and I, we loved that baseball." Another recollection of Covey’s "patchball" at recess time. "You’d throw the ball at runners, if you hit them, they’d be out. It caused a lot of fights." "I started first grade there—everyone was in one common class. My worst problem was my vaccination; I almost lost my arm. I had to carry it in a sling. |

Rev. Covey said he was disappointed that Jane Barclay didn’t make it to the reunion. "I grew up with her, it’s her dad the town’s named after (‘La" from Barclay’ and ‘Quin’ from ‘Quinn’). Stanley Barclay lived in the house up the road. It was a beautiful house. The rest of the houses were unpainted, but livable.

"I remember the day electricity came to town," Covey said, his memories flowing happily. "Stanley Barclay got a ‘dynamo.’ It was a big even in town.

Covey’s grandmother, Alice Dale, was both mid-wife (She’d stay with people until the doctor came) and Sunday School superintendent at Laquin’s Methodist Church. "Claude Mapes used to let me ring the church bell. He lived here when there was no more town."

Continuing, Covey said, "My Uncle Clyde and Uncle Ted Dale worked in the charcoal shed. I would walk up the tracks to meet them when they came home from work. They’d always have a little tidbit in the pail they carried on their shoulder."

Rev. Covey spoke of the hard work at Laquin, but recalled that "the big majority of men slacked off for a couple of weeks during the hunting season…the deer were enormous back then."

Mearl Dale also began first grade at Laquin. "My teacher was Mable Jefferson, I think." Mrs. Dale remembers being in Lola Long’s music class during later years. "I hated it. I did like to hear Mrs. Long sing; she had a very nice voice."

Of her family home she recalls: "The house was cold inside, they weren’t well built. The ones down-town weren’t painted…they had no cellars. Our water came down from the mountain."

She said she can rmember seeeing Mr. Barclay often, but that "Quinn never came around much."

A favorite recollection of Mrs. Dale’s: "We’d go to Towanda to see a movie. It was quite a drive in the wintertime."

William Hubbard said he recalls boyhood antics with Lloyd Eddy. "We’d play and wrestle by the hour. Our house was right across the creek from their’s." Hubbard was born in Laquin in 1910, his father was superintendent of the sawmill yard.

Hubbard said that it was "wonderful" to be back in Laquin among old friends.

Laquin—History

A PEN PICTURE OF LAQUIN, PENNSYLVANIA Author Unknown

Now I’ll spin you a yarn of a town called Laquin,

Though if ‘twas named Hell it would not be a sin;

For of all the bum places I ever have seen,

This town on the Schrader is surely the Queen.

‘Twas built in this valley on account of the mill,

And if it had a wall around it, ‘twould beat Cherry Hill.

For they work for their board here and buy their own clothes,

And they’re covered with sot from their head to their toes.

Now the streets here are paved, you can bet they are nice,

In summer it’s mud; and in winter it’s ice;

And the nights here are black as the hinges of Hell,

And if one takes sick here, he never gets well.

There’s a plant in this town, it’s called the stave mill,

It’s way up the track at the foot of the hill;

And if I were to tell you what these men have to do,

When you get to Laquin you would surely pass through.

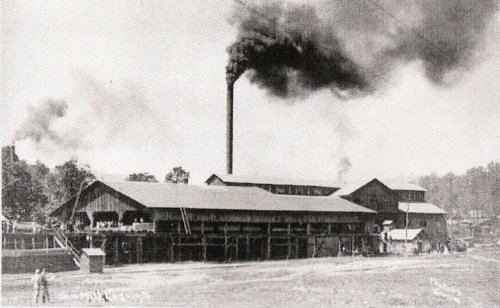

Then there’s the big mill and the hub factory too,

And the kindling wood joint where the girls dress in blue.

They are all just alike right down to a man;

They will take the last drop of your blood, if they can.

And of the distillery, a verse I will sing;

They make liquor of basswood or any old thing.

That the men drink it days and keep fire with it nights,

But it beats Laquin whiskey so far out of sight.

Now there are, of course, some good men in this place,

And some awful specimens of God’s human race;

And if the plain truth of these people you say,

They all live in Laquin for they can’t get away.

A doctor lives here and his name is John Doe,

He measures his dope always just so

And he’ll send you a bill that you never could pay

If you worked in this town ‘til your hair turned gray.

Another John Doe is a wonderful man,

Who does for the Company, all that he can;

For he’s built him a mansion far up on the hill,

So he gets a good view of the men at the mill.

Then there’s also John Doe who came from the South,

You wouldn’t think butter could melt in his mouth.

He will give you a job, if you’ll trade at his store;

You know what that means, so I’ll say no more.

Now a company store is, of course, ‘gainst the law,

And this one’s the worst that the world ever saw;

For they’ll double and treble on goods that they sell,

And if this crew don’t get there, there’s no use of a Hell.

Well the men here aren’t suited, at least so they say,

And I guess it’s the truth, from the wages they pay.

It’s a dollar and fifty; go look where you will;

A man could do better in an old shingle mill.

For they hire Italians and Huns by the score;

A white man can’t get a job there any more;

And if there’s a chance they will give you the run

And fill your place with an Italian or Hun.

And the time they keep is a sin and a shame;

They work these poor Huns in the snow and the rain

And they expect to keep running for a hundred years more,

Till they clean up Hungary and Italy’s shore.

But there’s Leo McRaff, no harm would he do,

And good Arthur Snell and Jack Anderson, too.

And Rockwell and Bademan are square as a brick,

Now on such men as these, we’ve no reason to kick.

And there’s Ellison Bennett, from Towanda he hails,

He’s a sawer of boards and a driver of nails.

At building new houses he’s going a fright;

It’s a blueprint in the morning and you move in at night.

And we’ll mention Sam Doe, he’s a dealer in beef,

If you buy meat of him you will soon come to grief,

For the steers that he sells and guarantees fat

Are bull meat unloaded at Mount Arrarat.

Then there’s another fellow, it’s butter he brings,

And pork and potatoes and lots of such things.

There’s more we might mention but what good would it do?

For hucksters in general are a dishonest crew.

Then there is Fred Flick, drives the Company’s blacks;

He goes ‘round through the streets as if hitched to a hack.

He’s the neatest thing, so the girls here all say,

That they’ve seen in Laquin for many a day.

Now the ladies in Laquin are fair as the rose,

And why they all stay here, God only knows;

If they lived in Cold Spring it wouldn’t seem queer,

Or in any old place just to get out of here.

Now there’s a crib here that they call a hotel.

A man can’t live long on the stuff that they sell,

For they make their own whiskey, and brew their own beer,

And if Bull isn’t rich it is certainly queer.

On the Company’s camps the bark peelers kick

And there’s one thing certain; the bugs are too thick.

The cooks are all Dutch, you plainly can see;

And often you’ll get a bed bug in your tea.

The men here in Laquin sometimes get so drunk,

That they don’t know whether they’re in Ralston or Shunk,

And the best thing to settle their poor muddled brains

Is the coffee they get up at good Mrs. Kane’s.

Now this worthy lady was never afraid

Of any human being that God ever made;

But if a small mouse in the dining room is seen,

She can jump on the table like a girl of sixteen.

And the girls that she keeps are good waiters and cooks,

They are jolly young people—you can tell by their looks,

For they serve you the grub in a way that’s so neat

That a corpse would get out of it’s coffin to eat.

Then there’s John Doe who runs another hash plant;

He’d take all the boarders in town but he can’t,

For his house is so full, I’ve heard it said

That they now have to put three or four in a bed.

And there’s Board Master Barnes, a God-fearing man,

For he gives us fish whenever he can,

And if he was able much more would he do,

But the boarders he got are the devil’s own crew.

Now to save the whole town from utter disgrace

They are building a church or two in this place,

And they’ll convert these poor heathen for one dollar a head

And guarantee them they will wear wings when they’re dead.

The Baptist preacher, from Elmira came,

As a builder of churches he gets there just the same!

The ground is now broken and the church under way,

And we expect the new spire to be seen any day.

And the Methodists too, are not far behind,

They are getting things fixed just about in their mind.

Their chaplain’s named Miller; he’s a Burlington man

And he’ll put a ringer in here if he can.

These city-bred preachers will call at your place,

And they’ll read in the Bible with a long solemn face;

They will ask you to church where they’ll pray and they’ll sing,

But when they get home they’ll do any old thing.

Now these sinners in Laquin are doubtless the cream

Of any in the country that ever were seen.

And if they can get them here so they’ll hear a church bell,

They can tackle any place this side of Hell.

For we wicked old hicks must someday walk the plank

And the chances are that we’ll draw a blank,

But if Gabriel should give us an old harp with one string,

We’ll just do our best with the angels to sing.

But if we had the choice of going to Hell,

Or staying on here for a much longer spell;

We would get out of town on the first sulphur train;

For if you die in Laquin, you go there just the same.

Now on the things past it’s no use to repine,

Though we’ve squandered our money on women and wine.

If we had it all back, we would borrow some more

And buy a through ticket to Africa’s shore.

And if I should live till I draw a full pay,

I’d leave this blamed town on that very same day.

And I’d hit the old hay road to York State once more

And bid farewell forever to the Schrader’s cold shore.

LIFE IN LAQUIN LONG AGO….ACCORDING TO 96 YEAR OLD DAISY EDDY

By Kathy Myron—Staff Writer—The Daily Review—July 29, 1987

Folks didn’t seem to mind the terrible odor from the chemical plant that pervaded the lumbering town of Laquin just about all of the time, Daisy Eddy recalls.

"People didn’t care; they like it. It was work they wanted."

Mrs. Eddy, though 96 years old, has amemory that barely skips a beat. "My family moved there in 1906 from a little village named ‘Jenningsville’ near Mehoopany. I was about fourteen. It was home and we had work. People were happy.

"It was a wonderful town…wonderful people," she continued. "My father worked on the mill saw. The mill whistle blew in the mornings at six; the men quit at six at night. They went on the hand-pump cart. All the factories worked Saturdays. The guys would dress up in suits and hats on Sundays—they couldn’t dress up any other day, they had to work.

"It was a boom town, nothing but work and push and go. The quicker they got the timber cut, the quicker they got their money. People spent it too! They didn’t try to save any.

"Herb Henry was paid most of anybody. He got $4 a day. He was a big man there. He rode the carriage in the mill and it was dangerous. Most workers got $1.50 - $1.75 a day."

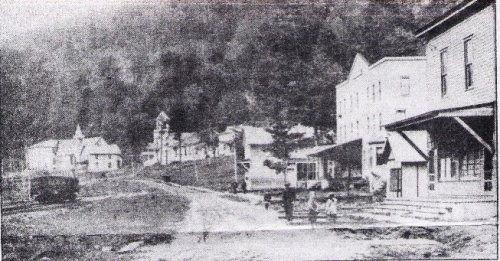

Smelly, Energetic. Noisy. Just what you’d expect from a baby; The bustling town, spanking new, was born just a few years before in 1902 in the narrow valley along the Schrader creek, just halfway between Wheelerville and Powell. Spawned from the twinkle of dollar signs in the eyes of several N.Y. entrepreneurs, its name was cleverly formed from a part of each of the names of two men prominently identified with the lumber company: Barclay and Quinn.

Mrs. Eddy remembers: "The people didn’t mind the noise. Mostly young and middle-aged folks lived there, not too many old people…lots of children. Trains were almost in your own yard. The railroad track ran right through the center of town," Mrs. Eddy reflected. "There was always smoke coming out of the smokestacks at the sawmill. We got used to it, we paid it no attention.

"They kept steam in the pond in winter time to keep the water from freezing so they could saw logs into lumber. It was so full of logs you couldn’t see the water.

"Sid Barclay was head man that bought the timber and ran the town. His father was superintendent of the mill and lumberworks; He was one of the big shots. They bought the big mountain of timber, Barclay and Quinn."

Mrs. Eddy easily finds words that conjure up a picture of the Barclay’s large and imposing frame house at Laquin. "It was a very special home they had built, very nice…a mansion."

Company owned cottages for the laborers were simpler. "Good, wooden houses, six or seven rooms, $6 a month rent. Uptown there was running water in the houses. We had kerosene lamps, wood and coal heat," Mrs. Eddy said.

| The History Center on Main Street, 83 N. Main Street, Mansfield PA 16933 histcent83@gmail.com |

|

|||

|