|

|

|

and Burials of Those Who Died There Burials in Woodlawn National Cemetery From the Elmira Prison Camp

|

The following article is from Our County and Its People - A History of the Valley and County of Chemung From the Closing years of the Eighteenth Century, By Ausburn Towner, D. Mason & Publishers, 1892 - Scanned and Formatted by Joyce M. Tice. Remember that this book was published in the nineteenth century when historians tended to gloss over any unpleasantness. The way history was treated in earlier times is a part of our history itself. Hopefully we are in a more realistic stage now and better able to deal honestly with the events of the Civil War era. For a more modern treatment of this subject see George Farr's 2002 Article

CHAPTER V.

Elmira as a Prison Camp -Its Establishment in 1864 Describing it and its Location - Arrival of the first Detachment of Prisoners A terrible Railroad Disaster -The appearance and condition of the Prisoners - How they were cared for in the Camp - The 11 Veteran Reserve Corps " - Officers in Charge of the Camp - Imaginary accounts of Escapes -False Alarms - Visitors attracted to the Camp-What could be Seen - The surroundings of the Camp - How the Prisoners occupied Themselves -The appearance of the Interior of the Camp Providing food for the Prisoners-Sickness and mortality Prevalent - The dead at Woodlawn - John W. Jones, the Sexton, who Buried them All - Breaking out of the Small pox -The disastrous Flood of March 17, 1865 - Burying the Dead - Means for their Identification - The close of the War and the breaking up of the Camp.

LOCATION OF THE PRISON CAMP 265

in May, 1864, at what had been called NO. 3 barracks, the ground it occupied, about thirty acres in extent, being on the western confines of the city of Elmira lying between Water street and the river. The northeast corner of the premises was a few hundred feet west of what is now Hoffman street and thirty or forty feet south from Water street. The fence along the northern boundary, built of twelve-foot boards standing upright, ran for about 1000 feet west from this corner, keeping at the stated distance from Water street. Nearly opposite to what has long been known as the Foster House ' were the main gates to the premises, great wide, high, thick, heavy structures that swung open and shut with many a growl and snarl. just at their side to the west was a small narrow gate for those on foot. In front of these gates and at their sides or near them, night and day, were numerous United States soldiers, some of them on guard duty, others waiting to serve at the same, others there for companionship or gossip. A wooden pathway two or three feet wide, with a hand rail built up on stilts on the outside of the fence and close to it high enough for the sentry who constantly paced along it to have a clear view of the interior, ran along the north side. There were sentry boxes at intervals along this pathway, and also flights of steps here and there to the ground. A fence similar In height with a like pathway for the guard ran south from the corner named in rather an uneven and irregular course, over the outlet to the pond inside, down to the bank of the river for a distance of about 800 feet. On the west side also the fence ran from the northern line down to the river bank, the distance being about 1000 feet.

There are broad fields now under cultivation on this spot, one of the most fertile and favorably situated in the whole valley, with here and there a dwelling or a newly opened street. Every vestige of the situation as it was now nearly thirty years ago has disappeared, and the busy military- looking scene is changed to one as peaceful and quiet as are the cattle grazing in the meadows or the calm sheet of water shining still and placid tinder the summer sun.

A little west of the great gates leading into the camp and lying between the high fence and Water street were the offices and quarters of the officers, long, low, one-story wooden buildings rude in construction, but made as comfortable as possible, in many instances decorated and ornamented with vines and some of them painted, most of them, however merely whitewashed. The soldier hospitalities of these temporary homes of the wives and families of the officers in command are recollections connected with these war times that are pleasing to many o the citizens of Elmira and its surrounding neighborhood, and the names of Col. Stephen Moore, Colonel Donovan, and Lieutenant- Colonel Crocker with others will be held in kindly remembrance for many a day. Elmira was selected as a place for the confinement of prisoners captured for the same reason that it was chosen as a depot for volunteers-its accessibility. It was easily reached by railroads from any direction and especially from the south, and at the same time it was so far removed from the scenes of conflict that there was no possible danger of its ever falling into the hands of the enemy.

The first detachment of prisoners arrived in the latter part of June, 1864. They came around by the way of New York city up the Erie Railroad. They met with a serious disaster on their way. While standing on a switch at Shohola, on the Delaware division, their train was struck by another train with most deplorable results. Sixty-four of the prisoners and sixteen of their guard were killed. Life was cheap in those war times and this terrible occurrence attracted comparatively little attention. A railroad accident these days in which the lives of eighty persons should be sacrificed would be heralded all over the world as a disaster of unparalleled magnitude. The bodies of the dead were buried near the scene of the awful occurrence. Afterward an officer was sent to remove them to Elmira, but it was ascertained that the graves were all in the State of Pennsylvania, and the officer, being under the authority of the State of New York, decided that it was not his duty to remove the remains and they lie t here till this day. Other detachments continued to arrive in larger and smaller numbers during the year. There were not many who could be called hearty, robust, or vigorous men. The much larger proportion were sick and disabled and very old or very young men. One of the earlier detachments, which contained not one perfectly well man, came from Point Lookout, where the water was bad and the worst species of malaria prevalent.

The first detachments attracted a great deal of interest and curiosity and unmistakable sympathy rather than any other feeling, and these

RECEIVING AND CARING FOR THE PRISONERS .267

were never entirely abated even to the last, a detachment being met at the railroad station by throngs of persons drawn thither to look upon the " rebels." As a rule they were all forlorn and unhappy looking men, spiritless in movement, and expressionless as to eye; poorly clad, .even ragged, emaciated, hollow-eyed, tired creatures, some of them scarcely able to move. There is in recollection as an illustration one aged man who found it impossible to keep up with his comrades, although the whole detachment moved very slowly up Third street from the railroad station down. Main and up Water to the camp. He was left behind guarded by three stalwart soldiers to be brought along as he could go, perhaps to be carried. He sat down upon the curbstone many and many a time by the way, and often apparently so exhausted it seemed as though he would never again arise voluntarily to his feet. He was rejoiced to arrive at length at the camp, where he could get a good meal and lie down. The aggregate of all the detachments arriving for the year and confined in the camp was 11,916 men, the large proportion of them being from North Carolina, although every State South had representatives in the number.

When the first detachments arrived all preparations had not been completed for their proper housing, although the feeding of them had been sufficiently attended to. The high fences about the grounds were not entirely completed and the shelter provided was only in the shape of ordinary "A" tents. But they were banked up, (it was in the summertime,) and they supplied quarters quite as good if not more comfortable than were given to soldiers in the field. Substantial wooden barracks were speedily built and before the winter had set in with any severity all were comfortably housed.

There was great care taken and much vigilance exercised in guarding the prisoners lest they should escape. At first there were portions of two infantry regiments of the regular army and a battery of the Fourth United States Artillery on such duty. These were succeeded by the Nineteenth and First Regiments of the " Invalid Corps." This corps was recruited in 1863, the idea originating in the office of the provost-marshal-general. It was comprised of men not fit for active duty in the field, but competent to serve at the headquarters of provost- marshals and such other light duties as did not take them to the front. The name was not a very fortunate selection, for it did not at all describe the character or condition of the members of the corps. It was therefore changed in 1864 to the " Veteran Reserve Corps," which had at least a much more honorable sound. The two regiments of the Invalid Corps guarding the camp of the prisoners were succeeded by the Twelfth "Veteran Reserve Corps," commanded by Colonel Moore, who remained until the camp was broken up. Colonel Moore readily became a favorite in the military and social circles of the town. At the conclusion of the war he kept a popular summer hotel on Lake Keuka, and then for some time was the proprietor of the Fassett House in Wellsville, Allegany County. Fie was an exceedingly competent and careful officer, and while under his control the camp was kept in the most perfect and orderly condition. He died in Wellsville, Allegany County, N. Y., August 29, 1891.

There have been circulated from time to time some stories, curious from their improbability and inaccuracy, in relation to a "dead line " in this camp, a line marked out on the interior a rod or more from the fence, stepping over which toward the fence was a sure warrant for. the death of such an offender at the hands of any of the guards patrolling the pathway along the outside. As regards the camp in Elmira there was no such line ever in existence and no occasion for it. There was never even an organized attempt of any extent to escape. A dozen or so of the prisoners once began a tunnel, but by a miscalculation or in their hurry the exit end of the hole did not reach outside the fence and the effort was a failure. It was claimed that two or three succeeded in digging out and escaped, and that it was not known to the authorities of the camp until a letter was received from one of the prisoners so escaping from a distant point giving an account of how they got away, and of their lighting a fire on West Hill from where they watched the commotion the discovery of their flight occasioned ! The continuation of the story was to the effect that the fugitives somehow or other got back to their regiments just in time to be killed in one of the later battles of the war around Richmond. Such tales are but the emanations of the brains of those whose fancy and imagination are more strongly developed than their love for truth, or they may have been the invention of those who for one reason or another sought to throw discredit on the management of affairs at the camp and the vigilance of the guard.

GUARDING THE PRISONS 269

Once or twice as a matter of discipline, and perhaps as well to vary the dullness and monotony of the camp, the commandant started an alarm, for which there was no foundation, of a general attempt at escape by the prisoners. It would show him how his men would act in case a real effort of that nature should be made. There was a terrible time for an hour or more. Orderlies and aids were bustling here, there, and everywhere. The guns of the battery were got in position to sweep the supposed point of outbreak, the infantry were all under arms and in line ready to march to any spot, and there was great noise, confusion, and bustle along the streets and in the meadows adjoining the camp. The commandant was satisfied that the force under him was on the alert and vigilant, declared the alarm a false one, complimented his officers and men on their attention to duty, and dismissed them, while within the grounds the prisoners were quietly sleeping and dreaming of anything rather than breaking through the guards that surrounded them. They never had any intention of trying to escape in a body by a sudden outbreak. Those were times of excitement, apprehension, and uncertainty such as those of the present generation find it difficult to understand or appreciate. Only the year before the Confederate army had come so far into Pennsylvania that their campfires could be seen from the city of Harrisburg, and that city is only a few hours by rail from Elmira. When the greatest number of prisoners were confined in the camp, and popular apprehension, ignorant of what that was in reality, more than tripled it, there were frequent disturbing rumors that the enemy were again approaching and for the purpose of liberating the prisoners and adding them to their own forces. The folly and impossibility of such an undertaking is well understood now, and is entitled to the ridicule and sneer that even its mention may excite. But it was not understood then, and there were apprehensions, groundless, however, as it all turned out, that the valley might become a portion of the scene of the war.

The prison camp in its first few months was the showplace of all the region of country for miles and miles about Elmira. Daily groups and companies of sight-seers came to look upon it. Along Water street on the opposite side of the grounds was a long row of rude wooden booths like those at a fair, or more like those that spring up in a night along a street that is the route to the grounds where a circus tent is to be spread. The stocks exhibited were also similar, there being for sale cakes, lemonade, peanuts, crackers, beer, and sometimes stuff considerably stronger than beer. Some one eager for an extra penny, one of that kind who would hardly have hesitated at making a peep-show of any sacred thing if there was money in it or of gathering stamps out of the distress of others, built at the northwest corner of Hoffman and Water streets a tall, square tower of sufficient height to view from its top the whole interior of the prison camp. The top was level and securely railed off, was supplied with chairs and spy-glasses, and a small admission fee was charged to ascend thereto with the privilege of remaining as long as you liked. One who visited this eyrie has left this record of the hal hour spent there with some rural friends who were eager to see all that could be seen. It is a reminiscence deserving preservation:

A full and complete view of the whole interior of the camp was presented. It was like looking down into an immense bee-hive. There was a constant motion on all sides, but without noise or confusion that could be heard. Groups were standing here and there, formed one minute, broken up the next; some men had built a fire underneath a tree and were baking corn-meat cakes; some one was coming or going every instant to or ' from every building whose entrance was in sight, and many were seated in the shadow of the trees whittling or fashioning some object, the character of which the distance forbade making out. In the space between the buildings and the fence nearest sat a small circle of men, with one on his feet who seemed to be speaking and making the most violent gestures. When he finished he seated himself in his place in the ring and another one rose to go through similar exercises in his turn. A few feet from these were five men playing cards. In the corner close at hand was a large tent that had a very lonesome look. Into it, during the half hour of the visit to the eyrie, came two men five times, bearing each time on a stretcher the dead body of a man covered over with a piece of canvas.

The booths on the street and the tower in the corner did not remain long. They were ordered away by those who had command, and they went. Visitors, however, did not cease coming. Townsfolk in their afternoon or morning drive or walk went up to the camp as a regular

HOW THE PRISONERS BUSIED THEMSELVES 271

exercise; strangers in the city always visited it, and many came from all parts of the country with no other purpose in view. Yet only the outside was visible to most of those who came. Very few indeed, as was proper, were permitted to enter the great gates and look within or witness the life of the prisoners. There was nothing to see save the high fences bounding the grounds on every side and the sentinels pacing monotonously up and down with bayoneted guns at their shoulders. Fortunate did the visitor consider himself if, as the great gates swung open to admit a team or an officer on horseback, he caught a momentary glimpse of the interior. Hundreds of those who came to view the place, or who lived within sight of it or within hearing of its noises, knew not so much of the interior of the camp as will the reader of this chapter.

The occupations of the prisoners during their confinement were as various as were the tastes of the men themselves, and such as they themselves chose, their only duty daily attendance upon morning and evening roll-call with here and there willing ones detailed to bake or cook or care for the grounds. It was said, and with truth, that those who kept constantly employed, were busy daily at something no matter how simple or unimportant in itself, were those who kept their health the best. The grounds were well cared for, the roads and paths being always in the very best condition, and a large and handsome lawn was kept the whole time closely shaven. About some of the barracks were some very beautiful flower gardens laid out in irregularly shaped beds with many border plants. having various colored leaves. Very much taste, skill, and ingenuity were shown by many of the prisoners in making a great variety of trinkets out of the shells of nuts, pieces of soft pine, straw, or horsehair. These were sold by some of the guard while off duty, and there are many relics of these times scattered all over the

country in the shape of watch chains and guards, small picture frames, fans, and ornaments of various kinds. A great deal of the furniture in the officers' quarters was made by the prisoners, most of it , being that of which the most skillful cabinetmaker would have no need of being -ashamed, and some of it by its beauty and curious formation would have deserved a place in any parlor, especially in these days of searching for what is odd and uncommon. The prisoners by their work not only occupied their time, minds, and hands, but provided themselves with personal funds with which they obtained credit at the sutler's, one of whom was established within the camp.

Where the large quantity of horsehair was obtained out of which so great a number of trinkets was constructed was a mystery for a long time, which the tails of the horses of contractors and others permitted within the enclosure eventually revealed. Col. Samuel B. Hayman, who was the acting assistant provost- marshal general of the division stationed in Elmira during the closing months of the war, rode into the camp one afternoon to confer with the surgeon in charge on some matter of business. He was detained very much longer than he expected, giving the person who had accompanied him an opportunity to examine the premises somewhat thoroughly, some of the results of which appear herein, and to find that the men confined there, except in the absence of their liberty, seemed to be in want of nothing else. Colonel Hayman had ridden into camp and hitched at a post some distance from the entrance a handsome and favorite white horse of his, much of whose beauty consisted in a flowing mane and an especially profuse tail. There was something besides the usual summer flies that kept the animal uneasy in the warm June day. The colonel discovered it when his visit ended; he came down to mount and could hardly recognize his steed. There were not to exceed five lonesome hairs left in the poor stump of a tail, and the mane, what there was left of it, looked like the head of a man who had been scalped! For a long time thereafter the watch chains, finger rings, brooches, and other ornaments that came from the prison camp looked more delicate and frail than usual, being made of white horsehair; but the colonel, whether or not he made an effort to do so, never discovered the person or persons who so denuded or detailed and de-maned his handsome charger.

Something deserves to be said of the food provided for the prisoners. In quality it was of the best and in quantity even profuse. John H. Leavitt, a long time and well regarded citizen of Elmira, after the war for many years the superintendent of the Elmira Water Works Company, and who died in 1890 was connected with the quartermaster's department of the post while the prison camp was in existence. He has left it on record that he virtually saw every pound of the rations or food issued to the prisoners. Great plenty reigned and of a good, sound,

SUPPLIES FOR THE PRISON CAMP 273

solid, substantial kind. In the year of the existence of the camp there were nearly 13,000 barrels of flour issued to and consumed by the prisoners, flour being issued instead of bread, there being a great 'saving thereby, some of the men being detailed to do the baking. The amount of meat, salt and fresh, issued in the period named was nearly 2,000,000 pounds. The plentiful supply for the prison camp is further testified to by the fact that there were large savings from the rations allowed by the government after the prisoners had had all they needed. These savings were turned into cash and went of course to the benefit of the prisoners themselves, making what was called a prison fund." It was in charge of a board composed of officers of the post and enabled the prisoners to have potatoes and other vegetables in their season ; fruit and delicacies for. the sick, which the government did not furnish - to improve and beautify the grounds and buildings; and do many other things that they would have been unable to do without it. The generosity and liberality in the matter of rations and the savings therefrom are still further shown by the fact that when the camp was broken up there remained in the batik to the credit of this prison fund the magnificent sum of $92,000 ! A draft for this amount was sent by Captain Sappington, the commissary of subsistence at the post, to Washington as almost the last act of his duty in Elmira. Divided among the prisoners this amount would have given each of them about $10.

It could not very well have been otherwise than that much sickness and great mortality should have prevailed in t e camp. As has been intimated the condition of the men on their arrival was very bad. The change of climate, the water, the difference in the manner of living, and the enforced confinement did not tend to improve the matter. One complaint recognized as a disease, home-sickness, was exceedingly prevalent. The art and skill of the physician are powerless before this distemper. It may not itself be fatal, but it is an open door through which more serious complaints find ready entrance to the system.

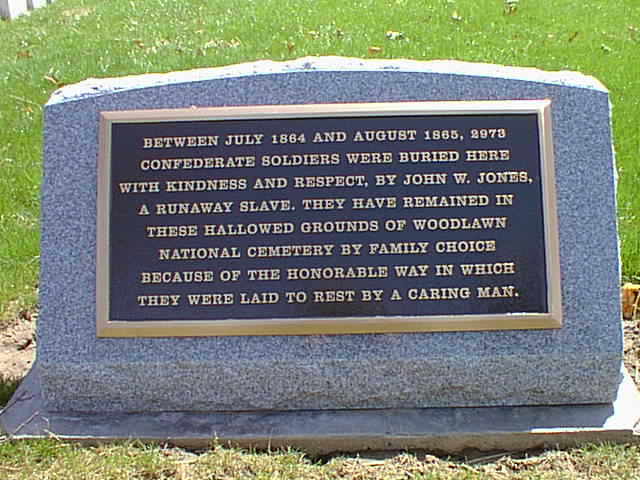

A death occurred soon after the arrival of the first detachment, and as an illustration of the haste with which the camp had been established, and the want of complete preparations for caring for the prisoners, there had been no arrangements made for the proper disposal of the dead. Perhaps it had not occurred to those in authority that any of them would die. What to do with the body of the dead soldier was not determined for some hours. It was put in an ambulance and taken to the headquarters on Carroll street, until the commissioners of Woodlawn gave permission and authority to bury it in their grounds. It taught those in command that their duties did not solely consist in caring for the living, but as well demanded their attention as to the proper disposition of the dead. A portion of the Woodlawn Cemetery was therefore set apart for this purpose. Here were laid 2,988 of the prisoners, all of them buried by the sexton of the grounds, John W. Jones. There is something rather suggestive in the fact that the last rites of so many of those who had been enlisted in an effort to preserve slavery as an institution of their country should have been performed by one who had escaped from that slavery and was a representative example of what freedom could do for the colored man. John W. Jones, with his brothers Charles and George, came to Elmira from the neighborhood of Leesburg, Va., in 1843, walking the whole distance Of 300 miles excepting eight miles, when they hired a ride from a farmer, in fourteen days. He was the sexton of the Baptist Church in Elmira for nearly half a century, giving up that position in 18go, and has accumulated a property to a very respectable amount.

The deaths in the prison camp aggregated -the number Of 2,994. Of those already named 2,988 were buried in Woodlawn ; three were buried on the bank of the river, but were washed away by the flood (hereafter to be referred to); and three more were buried in the neighborhood of the pest-house, down the river from Elmira, where they still remain. In detail, in the month of July, j 864, there were i i deaths; in August, 115; in September, 386; in October, 282; in November, 2 20 ; in December, 269; in January, 1865,.293 ; in February, 434 ; in March, 495 ; in April, 269; in May, 133; in June, 54; in July, 30; in August, 3.

Pointed tops are

Confederate and rounded tops are Yankee.

Pointed tops are

Confederate and rounded tops are Yankee.

In the spring of 1865 the small-pox broke out in the prison camp. Between 300 and 400 died of the disease. The sanitary measures of the camp were as perfect and complete as they could be with such a large number of men confined in so small a space. There was a pond of living, running water extending nearly across the grounds parallel with the river. Between this pond and the river, and nearest to the river, were

THE SMALL-POX EPIDEMIC AND THE GREAT FLOOD. 275

located the hospitals for those sick with the small-pox. The living barracks for the prisoners were across this pond 900 or 1,000 feet away to the north. The other hospitals for the ordinary sick were in the far

northwest corner of the grounds. These were large, airy, and well ventilated, and provided with every convenience that is seen in the best of such places No one confined within the premises need suffer for an instant for the want of any medicine or means of relief if he made his condition known. To add to the distress of the spring of 1865 came that remarkable flood so well' remembered in the valley of the Chemung, happening on March 17th, St. Patrick's day. The river rose with astonishing rapidity, and the small-pox hospital was soon surrounded and lay deep in the water, situated as it was near the bank of the stream. The situation for the sick was very serious, and to rescue them from their peril seemed at first impossible, the torrent swept by with so much force and with such an ever-increasing volume. But there were volunteers for the work. A few of the sick were brought over to the higher land in boats, a few only of which could be gathered for the purpose, but most were saved bymeans of the fences.' Two men. would seize the mattress on which a sick man lay, one at the head the other at the foot, and

doubling it up until fie within was almost hidden from sight make their way along the upper timbers of the fence to a safe and dry point out side the camp. After the waters subsided the sick were all returned to their quarters and the dead buried. The exposure doubtless increased the mortality for that month, in one day the number of cases of death having been forty, the largest number for any one day during the existence of the camp.

There was no attempt at any ceremonial at the burial of the dead from the prison camp, no services of any kind or character at the grave. Each body was put into a pine box and nine were taken to the cemetery at a time, just a good load for an ambulance. In a trench large enough to contain a number of these boxes they were laid side by side or foot to foot. On the top of each box was written the name of the person occupying it, his company, regiment, and State where from; this information, if it could be obtained, for not in every instance did the prisoner give his right name, although if he got into the, hospital he was pretty sure to announce it. Some curious instances of fictitious names are met with. One was borne on the record for some time as " Registered Enemy," the person giving it known by it until he was taken sick and was sent to the hospital. Then the bitterness that caused him to give such a name evaporated and he told his true name, Henry Matthews.

These names written on the tops of the boxes were copied by Sexton John W. Jones, and the location of each was recorded. Wooden headboards were erected on which was painted the information written on the boxes, but these soon totted away and the grounds in a few years presented a very dilapidated and forlorn appearance, not at all in harmony with the other portions of the well kept and beautiful cemetery. At one time there was a suggestion that permanent headboards of iron were to be erected, but it was never done. The grounds were surveyed, a map made, the location of each body accurately set forth, and now the plot is and for some years has been a fair smooth lawn with no evidences apparent that underneath the sod are reposing the remains of nearly 3,000 men. Twenty-five of the bodies were identified and reclaimed by friends.

An incident will well illustrate how the care for the living and dead at the Elmira prison camp was and still may be misunderstood and misrepresented. A year or two after the war a gentleman came to Elmira saying that he was from South Carolina and was in search of some tidings concerning his youngest son, who, as he said, had been in the Confederate army. It had been told him that the youth had been in the prison camp in Elmira and had died there. The gentleman came North to buy goods, and as he left his home his wife had put a letter in his hand which he was not to read until miles on his journey. Opening the missive at length the only words it contained were: " Bring our boy home with you." He had come to Elmira without hope of success, but willing to try. His astonishment and gratitude were unspeakable when it was ascertained that the name of his boy was on the record of burials with the name of his regiment and State. Further examination led to complete identification, and the mother's wish was gratified. There were other cases where bodies were reclaimed by correspondence, the record kept in the prison camp being so accurate and careful.

The gradual breaking up of the camp began very soon after the re

LAST DAYS OF THE ELMIRA PRISON CAMP 277

turn of peace. In the latter part of the month of June, 1865, came the order to parole the prisoners, not all at once, but in small detachments. The strongest and healthiest were first selected for release, the sick and those in the hospitals remaining, so that all were not gone until the latter part of August of the same year. Those who saw the first detachment marched down from the camp to post headquarters on Carroll street cannot soon forget the scenes enacted there. The prisoners knew, of course, that the war had ceased, but as to what was to be done with them they were ignorant and anxi6us. They were conscious of having been engaged in a rebellion that had been unsuccessful, and very naturally expected that some punishment was to be visited upon them. They did n't know when they were marched down to headquarters, fully guarded by armed soldiers, but what they were marching to their death, and there were many inquiries among them whether they were to be hanged or shot. When they were told that they were absolutely released from restraint their joy was excessive, but when added to this they were provided with transportation to their homes, and had their haversacks filled with rations in sufficient quantities to keep them in food until they arrived there, many were touched to tears that came from feelings that differed very much from sorrow.

The horrors of a camp where prisoners of war are crowded into a confined space, poorly clad, uncomfortably housed, insufficiently fed, and scantily provided with medical attendance, hospital accommodations, and other provisions for the sick, form one of the most deplorable features of any war, but none of these can apply with truth to the camp at Elmira, nor can they be attached for a moment to the reputation or become a portion of the history of the fair valley of the Chemung.

Burials in Woodlawn From the Elmira Prison Camp

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|